All Features

Akhilesh Gulati

Meritocracy—the idea that individuals should advance based on their talent and hard work—appeals to our sense of fairness. However, despite its noble intentions, meritocracy often fails in practice.

Emilio J. Castilla’s The Meritocracy Paradox (Columbia University Press, 2025) highlights how…

Chip Bell

One hour after takeoff from London’s Heathrow Airport on an intercontinental flight to the U.S., the pilot announced the aircraft was returning, “because my windshield just shattered.” After gasps from passengers, he calmly announced there was no danger, but there would be a long delay to secure…

Jeff Dewar

I’m thrilled to announce something we’ve been working on for a year and a half—a project that took us 30,000 miles across America and into the heart of industries that most people never see. On Nov. 12, 2025, Quality Digest will premiere the first episode of The Quality Digest Roadshow, a 12-…

Kate Zabriskie

When most people think about work, fun probably isn’t the first word that comes to mind. Deadlines, meetings, and spreadsheets? Sure. But laughter, camaraderie, and a little silliness? That often feels like a luxury, not a priority.

Here’s the truth: Fun at work isn’t just about blowing off steam…

Mike King

Change is inevitable in manufacturing. Controlling change effectively distinguishes industry leaders from quality-deficient, recall-plagued, and regulatory-troubled companies. As organizations are increasingly pressured to reduce costs while maintaining high levels of product quality, the drive to…

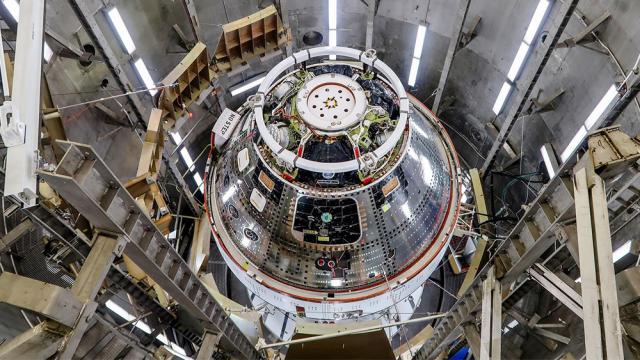

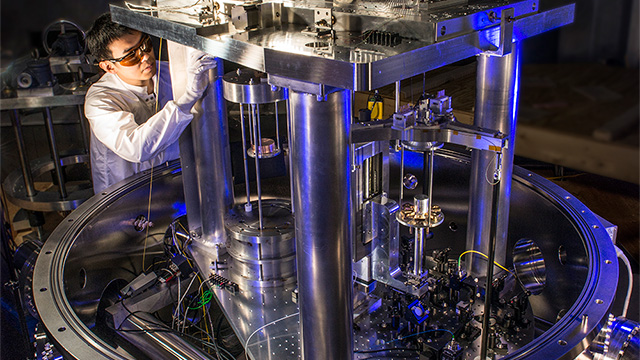

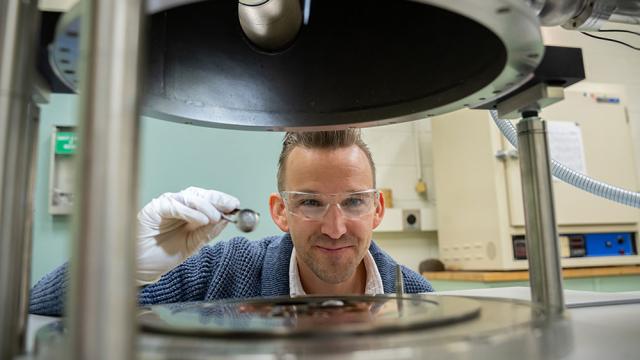

Dirk Dusharme

Literally, everything that surrounds us has been measured—and I do mean literally. Look around you: Your desk, your chair, your pen, your pencil, the lead in the pencil, the paint on the pencil, the gas in your stove, the stove itself—it’s all been measured. The color of your orange juice, the…

Chris Kuntz

What once seemed like the future of work is fast becoming present-time reality on factory floors worldwide as artificial intelligence (AI) evolves from experimental technology to practical tools that directly affect daily operations. While algorithms can predict when a bearing will fail or when a…

Creaform

In motorsport, performance isn’t defined by a single factor. It’s the sum of countless details, each playing a decisive role when pushing speeds up to 200 mph (320 km/h). From how a driver sits in the car to how the bodywork complies with strict regulations, accuracy can mean the difference between…

Rajas Sukthankar

Simply put, we live in a digital world—both in our personal lives and on the job. In manufacturing, challenges abound. Customization, fast-changing business and technology environments, and workforce and talent-pool concerns combine to present challenges for manufacturers of all types.

Among…

Stephanie Ojeda

When organizations implement an enterprise quality management system (EQMS), the instinct is often to begin with high-visibility processes like corrective and preventive action (CAPA) or supplier quality. While these functions are critical, starting there can be a misstep. Without the right…

William A. Levinson

My June 2025 article, “How to Avoid FDA Warning Letters,” points out that inadequate corrective and preventive action (CAPA) is a major reason for warning letters, and also introduces the role of failure mode effects analysis (FMEA) in preventing trouble in the first place. The U.S. Food and Drug…

Mike Figliuolo

I had a great conversation with a friend of mine. He was bemoaning the fact that his company was almost completely dependent on one huge customer. He saw the inherent risks in that relationship but confessed that his organization had a bad habit it couldn’t kick. It had succumbed to the addiction…

Alex de Vigan

D uring the past decade, manufacturers have wired their plants with sensors, robots, and software. Yet many “AI-driven” systems still miss the mark. They analyze numbers but fail to understand the physical reality behind them: the parts, spaces, and movements that make up production itself.

“…

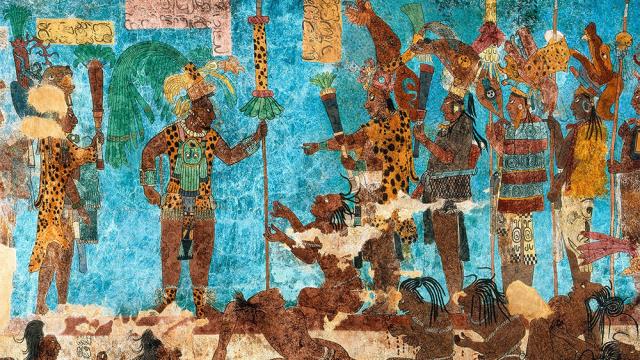

Harish Jose

In this article I want to explore an observation on how we make distinctions and what this reveals about the structure of our thinking. I’m inspired by the ideas in George Spencer-Brown’s Laws of Form and broader themes in cybernetics about how observers construct meaning.

The starting point is…

Lexi Sharkov

We’d be willing to bet your key collaborators aren’t all in the same building. Your team members, contract partners, clients, and suppliers are likely scattered across the globe. That makes collecting physical, “wet ink” signatures nearly impossible and turns digital approvals into a daily…

James J. Kline

The use of artificial intelligence (AI) models, specifically generative AI, is growing. This has raised concerns about the effects on jobs in various professions. The quality profession is among them.

Like it or not, the quality profession has been disrupted. This occurred before AI became widely…

Cassondra Blasioli

Growing up in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, I witnessed firsthand the heartbeat of American manufacturing. I remember the hum of machines, the rhythm of assembly lines, and the pride of workers crafting products that powered industries across the nation. I can still smell the oil and hear the machines…

Andrew Iams

I grew up outside Pittsburgh, widely known as “Steel City.” Although the city is no longer the center of steel or heavy manufacturing in America, its past remains a proud part of its identity.

Like many Pittsburghers, my family’s story is tied to this industrial legacy. My relatives immigrated…

MasterControl Inc.

Ninety days to implementation vs. 12 to 18 months with traditional systems: That’s not just an incremental improvement—it’s a complete reimagining of what’s possible in life sciences quality management.

In the highly regulated life sciences industry, quality management system (QMS) implementations…