All Features

Adam Zewe

A broken motor in an automated machine can bring production on a busy factory floor to a halt. If engineers can’t find a replacement part they may have to order one from a distributor hundreds of miles away, leading to costly production delays.

It would be easier, faster, and cheaper to make a new…

Mike Figliuolo

It’s nauseating to hear someone soft-shoe dancing around an issue because they’re afraid of hurting someone’s feelings.

They do so because they might receive negative feedback in a 360 review that they were abrupt or too direct in delivering feedback on that issue. So rather than going the direct…

Ryan Pembroke

Walk into any machine shop today and you’ll hear about the same pressure points: tighter deadlines, rising part complexity, a stubborn skills shortage, and customers expecting “digital-ready” suppliers that can turn work around without delay. It’s no surprise then that artificial intelligence has…

Oak Ridge National Laboratory

The U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) and Kairos Power have entered into a $27 million strategic partnership to accelerate the technology needed to deploy a new generation of advanced nuclear reactors and support U.S. nuclear energy goals.

Under the partnership…

Chip Bell

Delight your customer! Exceed your customers’ expectations! Provide value-added service! These have been mantras of customer service gurus for a long time. Such a focus on “giving more” has improved customer service quality in many organizations. It has also increased customer standards for what…

Adam Zewe

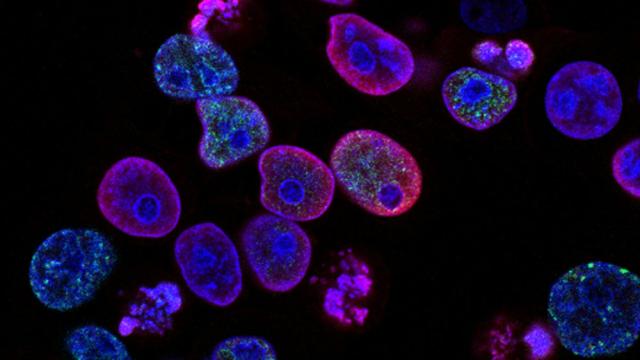

Studying gene expression in a cancer patient’s cells can help clinical biologists understand the cancer’s origin and predict the success of different treatments. But cells are complex and contain many layers, so how the biologist conducts measurements affects which data they can obtain. For…

Gleb Tsipursky

Transparency is not a luxury in today’s transformative projects—it’s a necessity. As organizations integrate generative AI (gen AI) into their operations, the importance of clear, consistent communication around project milestones and outcomes can’t be overstated.

Employees aren’t passive…

Chris Chuang

As manufacturing emerges from a period of contraction, the industry faces more than just empty roles. The average tenure of a manufacturing worker has dropped, but the complexity of the machinery hasn’t. While the industry sees signs of hope, we face a knowledge crisis far more dangerous than…

Mike Figliuolo

What’s the biggest risk facing the leaders of most entrepreneurial ventures? It’s not closing that first round of funding or landing a cornerstone customer. As with most things, it all comes back to people—and your ability to lead those who don’t have much practice following.

It’s easy to be…

Riley Wilson

From blood tests to mammograms, doctors need reliable measurements to make informed decisions about their patients’ health and deliver safe treatments. That’s why the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) serves as an important partner to health professionals and their patients…

Oak Ridge National Laboratory

In a long-running collaboration with GE Aerospace, researchers at the University of Melbourne in Australia have been steadily working to improve the performance of high-pressure turbine (HPT) engines through computer simulations on leadership-class computing systems. These turbines are the heart of…

Daniel Stewart

Imagine you’re a frontline worker. A new AI system has been rolled out on your line. You’ve heard that it boosts productivity, but you’re not sure how it works or what it means for your role.

Would you:• Spend 20 extra minutes entering data into it if you feel jotting notes on paper was just as…

NIST

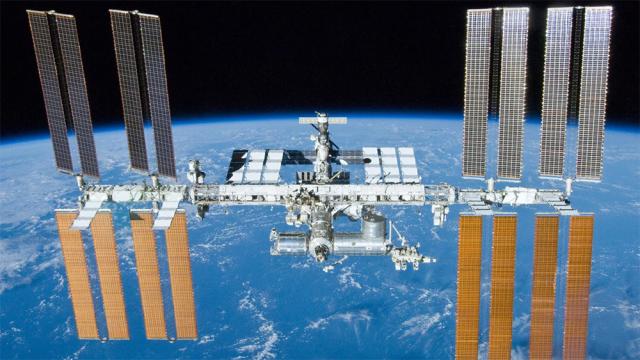

Wrapped snugly in a custom container, seven carefully chosen materials left Earth on Aug. 24, 2025, traveling at 17,500 mph. Nestled at the top of a Falcon 9 rocket, house dust, freeze-dried human liver, and cholesterol joined four other scientific specimens to travel to the International Space…

Jasmine Escalera

The traditional promise of work was simple: Support your life, care for your family, and build toward meaningful milestones like purchasing a home or saving for your children’s education. But for many modern professionals, that relationship with work is shifting. Instead of working to live, more…

Bruce Hamilton

In 1960, organizational psychologist Douglas McGregor introduced a conceptual framework of two contrasting theories about human motivation that grounded my Toyota Production System (TPS) learning.

His Theory X was based on the assumption that workers are fundamentally lazy and can’t be trusted to…

Adam Grant

Nano Tools for Leaders—a collaboration between Wharton Executive Education and Wharton’s Center for Leadership and Change Management—are fast, effective tools that you can learn and start using in less than 15 minutes, with the potential to significantly affect your success and the engagement and…

Megan Wallin-Kerth

Working with a disability can be a frustrating and isolating experience. As someone who spent years blaming vitamin deficiencies, anxiety, and even Covid for worrisome symptoms before finally seeing a neurologist—and then a movement disorder specialist, I can attest that even the lengthy process of…

Troy Harrison

What does onboarding mean? If you said “onboarding a salesperson” consists of doing the HR paperwork, giving a facility tour, a few days of shadowing existing salespeople, and then expecting the salesperson to hit the ground running, you’re not alone. Entirely too many sales managers feel that way—…

Akhilesh Gulati

A few months ago, during separate visits to an emergency department and an urgent care center, I experienced what many patients and clinicians now consider routine: long waits, crowded spaces, and visible strain on staff. It raised a familiar question that I’ve been asking for years: If the…

Adam Grabowski

Freedom is generally defined as the power or right to act, speak, or think as one wants without hindrance or restraint. The license to act as one pleases offers a host of benefits but can also produce consequences that limit your freedom. The same can be said of your manufacturing. The choices you…

Paige Orme, Maria DiBari

Capability maturity model integration (CMMI) is a process improvement framework required by many U.S. government contracts. If you’ve been through a CMMI appraisal in aerospace or federal contracting, you know there’s a typical pattern. Things look great on paper. Then the appraisal date gets…

Harish Jose

This article is inspired by the ideas of cybernetics, Martin Heidegger, and Nassim Taleb. I’m looking at what I think is the largest danger of large language models (LLMs).

LLMs are extraordinarily proficient in the domain of language, and that proficiency has quietly created a philosophical…

William A. Levinson

ISO 9001:2015 Clause 6.1 requires attention to actions to address risks and opportunities. There really is little practical difference between the two, as failure to exploit an opportunity constitutes a risk.

To put this in perspective, recall that poor quality is only the tip of the iceberg when…

Tzaferis Meleti

Let’s be honest. Conformity assessment has become dangerously comfortable. It’s familiar, structured, and predictable. It gives organizations a reassuring feeling of control because it produces clean documentation, tidy checklists, and audit reports that look professional. It also creates an…

Stephanie Ojeda

Integrating environmental, health, and safety (EHS) with quality management is no longer optional for manufacturers; it’s essential for achieving operational excellence, ensuring ISO compliance, and driving sustainable growth. Traditionally, EHS management and quality management systems (QMS)…