All Features

Creaform

The Bott Group designs vehicle and operating equipment as well as workplace systems. From its headquarters in Gaildorf, Germany, and two production sites in Bude, England, and Tárnazsadány, Hungary, Bott Group designs and manufactures work environments for mobile and stationary manual work…

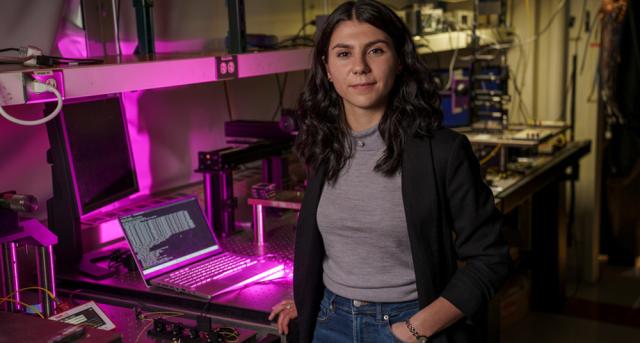

Stephanie Ojeda

Global-scale events have tested the bounds of supply chain systems. The coronavirus, for example, made it clear how critical an efficient supply chain is for continuity and survival. It’s a real-world example of how important it is to have an enterprisewide system that uses a quality management…

Joe Curcillo

Let’s start with the argument every aspiring leader loves to have, even if they don’t say it out loud: Specialist or generalist? Depth or breadth? That’s the fork in the road every ambitious leader eventually hits. And the farther up the ladder you go, the more that question lingers.

You’ve…

William A. Levinson

I recently needed to have a hot water expansion tank installed in my house. The first plumber who came to mind is widely advertised on local radio. The company’s online reviews suggest that they do good work, but one added that they are expensive—and it’s probably because they have radio ads…

Bruce Hamilton

I took a walk-jog this morning, something I’ve been doing pretty regularly since early June. Some days are better than others, and today started out sluggish. But as I turned the corner of my street, my neighbor drove by, rolled down his window, and gave me a friendly wave.

Almost like getting a…

Brookhaven National Laboratory

Ateam of scientists across several U.S. Department of Energy national laboratories has unraveled how light and a previously unknown form of certain nickel-based catalysts together unlock and preserve reactivity. This research, described in the journal Nature Communications, could potentially…

Nimax

Pharmaceutical serialization practices are on the rise and have progressively become a worldwide standard as a result of stringent regulations in various of markets, including the United States, European Union, China, and Argentina. Recent estimations found that by 2022 serialization practices had…

Ariana Tantillo

A new security screener that people can simply walk past may soon be coming to an airport near you. Last year, U.S. airports nationwide began adopting HEXWAVE, a commercialized system based on microwave imaging technology developed at MIT Lincoln Laboratory. HEXWAVE addresses a new Transportation…

Donald J. Wheeler

The engineer came into the statistician’s office and asked, “How can I compare a couple of averages? I have 50 values from each machine and want to compare the machines.”

The statistician answered, “That’s easy. We can use a two-sample t-test.”

“How would that work?” asked the engineer.

“We…

Creaform

Known for building rugged telehandler equipment that delivers reliable performance in the most demanding environments, Xtreme Manufacturing places a strong emphasis on quality in every stage of production.

To uphold its commitment to quality when inspecting large weldments, Xtreme needed a…

Oak Ridge National Laboratory

The U.S. Department of Energy’s Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) and JuggerBot 3D, an industrial 3D-printer equipment manufacturer, have launched their second research and development collaboration through the Manufacturing Demonstration Facility (MDF) Technical Collaboration Program.

The two…

Sam Schaffter

My grandfather was a carpenter, so growing up I often heard the adage, “Be sure to measure twice so you only have to cut once.” The saying is also attributed to tailors—you have to make sure your measurements are correct before you cut the fabric.

Little did I know that years later the saying…

Robyn Coward

In life sciences, every decision carries weight—and speed to market is an ever-present consideration. Scientific innovation is moving faster than ever, yet regulatory demands are growing more complex, and supply chain fragility has become the new normal. Within this volatile landscape, the role of…

Jennifer King

Although patient safety is paramount in healthcare settings, about 1 in 10 patients is harmed in healthcare, and more than 3 million deaths occur due to unsafe care, says the World Health Organization (WHO). The reality is hospitals and healthcare facilities face numerous challenges in managing…

Alexander Shipps

When ChatGPT or Gemini gives you what seems to be an expert response to your burning questions, you may not realize how much information they rely on to give that reply. Like other popular generative artificial intelligence (AI) models, these chatbots rely on backbone systems called foundation…

Etienne Nichols

Good supplier management is one of the most important methods of building a safe and effective medical device. A single device may be made up of dozens of parts and components coming from several different suppliers, and many medical device companies outsource the manufacturing of their device to a…

Automated Precision Inc.

CNC machine tool calibration is essential for machining precision and process reliability. Even a well-built CNC machine will gradually drift out of alignment due to everyday wear and environmental factors, leading to deviations in accuracy.

Without regular calibration, these small errors can…

Akhilesh Gulati

Complacency won’t show up on a control chart. But its damage is real. Can AI and systems thinking help us detect it and respond before trust is lost?

As customer expectations evolve, one question remains: Are customers still at the core of your company’s operations?

Back in 1999, a simple but…

Mike Figliuolo

This article is dedicated to all the paranoid businesspeople out there who are terrified of their competitors. You know, the people who run businesses centered around “consulting” who view any other “consulting” firm as a competitor. You can insert whatever industry you like in the quotes, and this…

Darren Metherell, Quality Digest

Quality Digest attended the 2025 Hexagon Live event in Las Vegas in June—and with that came the opportunity to speak with the great minds, creators, innovators, and sales teams of Hexagon. Darren Metherell, head of sales at Hexagon, followed up with the QD team after this event to speak more about…

Harish Jose

I’m further exploring the notion of models and mental models. We often speak of mental models as though they’re neat packages of knowledge stored somewhere in the mind. These models are typically treated as internal blueprints and as simplified representations of the world that help us navigate and…

Adam Zewe

Inspired by the Harry Potter stories and the Disney Channel show Wizards of Waverly Place, 7-year-old Sabrina Corsetti emphatically declared to her parents one afternoon that she was, in fact, a wizard.

“My dad turned to me and said that if I really wanted to be a wizard, then I should become a…

Winnie Jiang, Chiara Trombini, Zoe Kinias

The need for workplaces that are truly inclusive, caring, and equitable is growing. So how can leaders create an environment where employees feel empowered to help one another, support diversity initiatives, and contribute to community causes?

Prior research has linked this kind of prosocial…

Alexander Gelfand

A lecturer at Stanford Graduate School of Business for more than two decades, Robert Siegel says, “I’ve taught almost 20% of the people who graduated from the GSB.” He has also served as an executive at Intel and General Electric, founded and led startups, and worked as a consultant and venture…

George Schuetz

There are endless variations in the dials used on mechanical dial indicators. In most cases, though, they can be broken down into two distinct styles: balanced and continuous. Let’s look at both.

With a balanced dial, the graduations around the dial represent the smallest value, or resolution, as…