Content by Ken Levine

Tue, 06/16/2020 - 12:03

Lean Six Sigma (LSS) professionals have an enormous opportunity to add value to organizations and to our communities during this coronavirus pandemic. We have the objective orientation, methods, and tools to help. Process improvement is currently…

Mon, 07/31/2017 - 12:03

Completing the define phase of a lean Six Sigma (LSS) project is a critical part of any project, although it’s often underestimated in practice. The define phase of the define, measure, analyze, improve, control (DMAIC) process typically includes… How to Determine the Worst Case for a ProcessHave confidence in the confidence interval

Wed, 06/29/2016 - 16:56

How do you determine the “worst case” scenario for a process? Is it by assuming the worst case for each process task or step? No. The reason is that the probability of every step having its worst case at the same time is practically zero. What we’… What Really Is a ‘Stretch’ Objective?When working harder or longer won’t do the trick

Mon, 04/18/2016 - 13:34

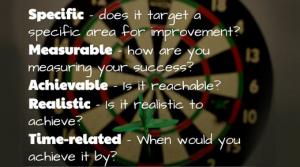

One poorly understood concept in lean Six Sigma is how much to “stretch” when setting S.M.A.R.T. goals. These letters are defined as S—specific; M—measureable; A—assignable, attainable, or achievable; R—realistic, reasonable, or relevant; and T—… Recycling Your Meeting WasteGood meetings are good for business

Mon, 01/16/2006 - 22:00

Lean Six Sigma and other continuous improvement initiatives require effective teamwork, and effective teamwork requires good meetings. Ineffective meetings are the reason many organizations fail to improve continuously. Therefore, effective meeting… Root Cause Analysis Takes Too LongPlan responses to service problems in advance and reduce the cost of the solution.

Tue, 11/15/2005 - 22:00

Engaging your workforce is a major obstacle in a lean Six Sigma implementation. Only a limited number of employees will initially participate in Six Sigma improvement projects. It can also take one to two years before all employees participate in a…