In this article I want to explore an observation on how we make distinctions and what this reveals about the structure of our thinking. I’m inspired by the ideas in George Spencer-Brown’s Laws of Form and broader themes in cybernetics about how observers construct meaning.

|

ADVERTISEMENT |

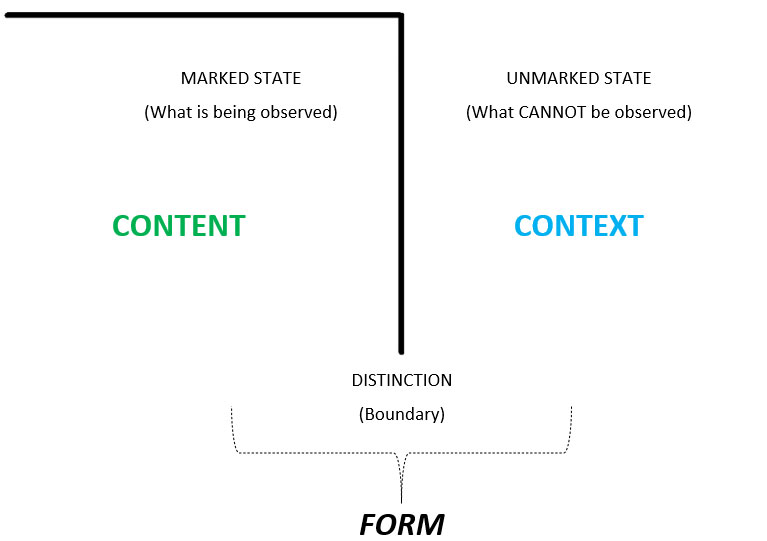

The starting point is simple. When we make a distinction, we create a boundary that separates what’s inside from what’s outside. Spencer-Brown formalized this with his notation of the mark, showing how any act of indication simultaneously creates both the indicated and the nonindicated. This is shown below:

As we look closer, things get more interesting.

The basic operation of distinction-making

When I make one distinction to mark “A,” I create two states. There is A (the marked state) and not-A (the unmarked state). This seems straightforward enough. We can depict this as below:

(A) not-A

…

Add new comment