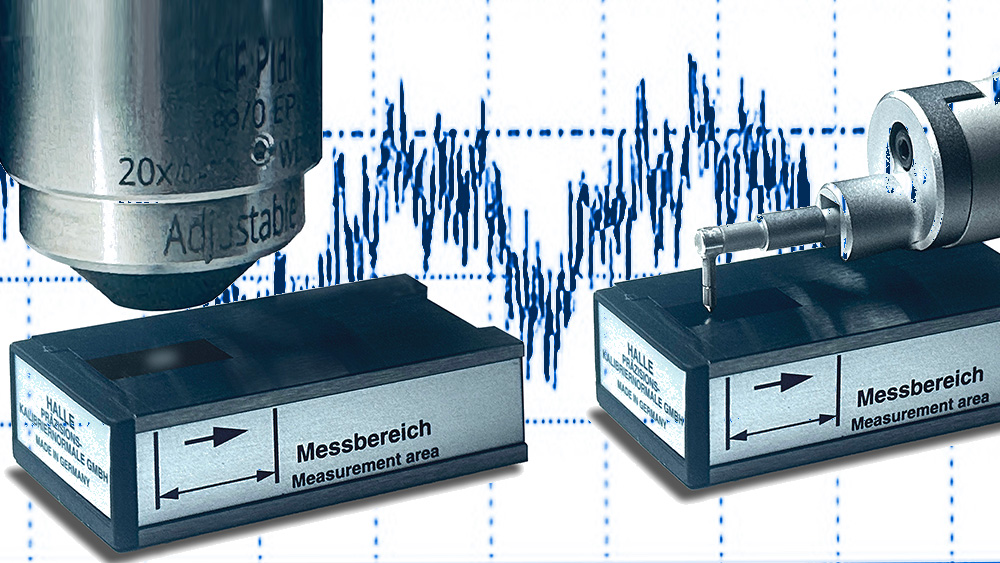

Choosing the correct instrument for surface texture measurement can be confusing, given the wide range of options. Stylus-based instruments are the most prevalent in manufacturing. Yet, measuring a surface with a sharp stylus can seem old-fashioned when so many noncontact optical techniques are now available.

|

ADVERTISEMENT |

In reality, both stylus and optical technologies have their place. Here’s a look at applications where each technique excels or has limitations.

Texture is more than roughness

Before we delve into surface texture measurement, it’s important to remember that surface texture is not a number: Texture consists of many “shapes,” which can be described as a spectrum of “wavelengths” ranging from shorter wavelength “roughness” to longer wavelength “waviness” and “form.”

…

Add new comment