In the first two episodes of The Quality Digest Roadshow, we looked at the evolution and use of dimensional measurement and measurement standards.

Distance is what most of us think about measurement. However, every day we use products that rely on another type of measurement—force: the amount of force needed to remove a screw-on lid or pop the top on a beer can; to peel masking tape off a surface; or how much force can be exerted before a rope, cable, or bungee cord breaks. Manufacturers use precision force measurement to test all these things and ensure that everyday products work reliably and consistently as designed.

Since screw-on caps aren’t particularly sexy, for this episode we found something that is. We look at how force measurement is used to measure a critical part on one of America’s favorite sports cars—the Corvette.

Like many high-performance vehicles, the Corvette’s handling on different road conditions is partly dependent on the suspension springs. Depending on the type of ride desired—firm to smooth—the springs need to be stiff or not-so-stiff. The measurement for this stiffness is called the spring rate. The higher the spring rate, the stiffer the spring, i.e. harder to compress.

We visited Van Steel in Clearwater, Florida, a leading manufacturer of aftermarket Corvette parts including composite springs to replace the steel leaf springs found on older Corvettes.

Corvette drivers can be picky about getting just the right spring rate, and it’s Van Steel’s job to make sure they deliver the perfect spring. To ensure that the springs are manufactured to the exact spring rate required by the customer, Van Steel tests its springs on a force tester. The force tester compresses the spring for a specified distance at a specific velocity and measures the force required to deflect the spring through that entire movement. Van Steel uses a Starrett force tester to make that measurement.

How a force tester works

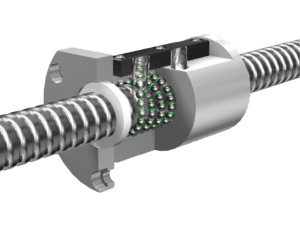

A ball screw converts the rotary motion of the screw into linear motion. Imagine holding a nut on a screw as you turn the screw. The nut will move linearly along the screw. The “nut” in the case of a force tester is the crosshead.

|

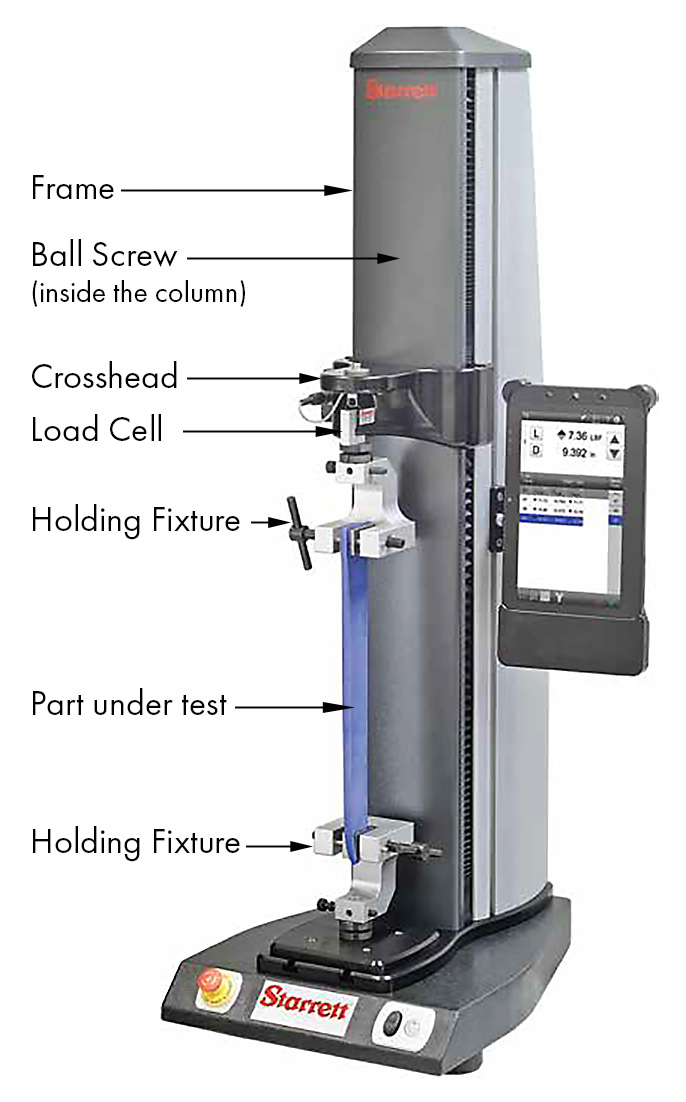

At it’s simplest, a force tester consists of a frame (stand), a motor that turns a ball screw, and a crosshead that moves up and down either pushing (compression) or pulling (tension) the part under test. The crosshead holds a load cell—an electromechanical device that converts force into an electrical signal, and some sort of gripper or fixture to hold or push against the part under test. The signal from the load cell is sent to a computer for processing and display.

Putting it all together, you have something that looks like the tester shown here. The motor turns the ball screw, which moves the crosshead and attached fixture up or down at a set speed. A rotary encoder attached to the ball screw precisely measures how far the crosshead travels. The distance the crosshead travels and the speed of travel are variables that can be set per the application. Depending on the type of test, the software will display results, calculations, and graphs in real time.

In the case of Van Steel’s spring rate test, the crosshead pushes into the center of spring, measuring the force through one inch of travel.

Type of tests

Here are just some of the tests you can do with a force tester.

Distance limit test

This test is used when you need to determine the amount of load the sample exhibits while being pulled or pushed to a distance setpoint. This would be the type of test used to measure spring rate. Van Steel’s test setup pushes the spring from 0 to 1 in., measuring the force throughout the travel.

Load limit test

How far has a sample stretched or compressed once it has reached a specific load?

Load hold test or distance hold test

Over time, how far does a sample stretch or compress while holding it at a specific load? This can be used for creep and relaxation testing.

Break/rupture test

This setup lets you create a break test by specifying the break value and the test speed. This test is usually used when you’re interested in determining the maximum (peak) load and the distance at the maximum load.

Cycle count tests

The cycle count test lets you create a test where the crosshead moves continuously between two set points at a specified speed.

A bit about accuracy

For force measurement, the accuracy of the load cell is critical, of course, with load cell accuracy typically 0.1% of the full-scale value (a 330 lbf load cell would be accurate within 0.33 lbf). But distance accuracy is also critical.

Although you might not need to know the spring rate of composite suspension springs to three decimal places, that kind of accuracy is required for some applications. That’s why precision force testers can measure travel distance to better than 20 µm. You might wonder why travel has to be accurate to micron levels. We discussed this in Episode Two, where a small error, when entered into an equation, can be compounded.

For instance, here’s the equation for spring rate:

Spring rate = lbf/distance traveled

If our target is a spring with a spring rate of 300 lbf/in. , the spring must measure 300 lb at 1 in. of deflection. If the force tester thinks it has compressed the spring 1 in., but it only compressed it 0.90 in., the tester would report a spring rate of 300—but the actual spring rate would be 333 lbf/in., about a 10% error. That amount of difference in the spring rate can be felt by the driver. And while that might not be a critical difference for an automotive suspension, for some medical devices, operating at smaller forces and more critical requirements, it could mean life or death.

Conclusion

Throughout this series we look at how everything gets measured, and why some measurements, even for something as seemingly mundane as a car suspension, have to be so precise. Anyone who works in manufacturing knows that products are being designed to tighter and tighter tolerances. These tighter tolerances allow us to drive cars longer, reach farther into space, and create medical devices that can be implanted in our bodies. These tolerances require more and more sophisticated measurement technologies to ensure the customer gets what they expect.

That’s why precision metrology matters.

Add new comment