The following is inspired by The Teachings of Don Juan (Washington Square Press, reprint 1985), an anthropological novel from the 1960s written by Carlos Castaneda, chronicling his travels with Don Juan, a Yaqui shaman. To crudely paraphrase, according to Don Juan, the road to knowledge is first blocked by fear of learning new ideas, an experience most of us have had to one degree or another on our lean journeys.

|

ADVERTISEMENT |

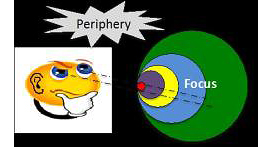

For those who forge ahead in the face of this “natural enemy” of knowledge, we are rewarded with “clarity,” a confidence we gradually acquire as we seek to learn. Clarity, however, becomes the second enemy of knowledge because its focus blinds us to new learning beyond a confined framework. Shingo called it complacency. I call it “too happy too soon.” The point is when we are too confident with our understanding of continuous improvement, new learning stops. With that preface, here is a story.

…

Add new comment