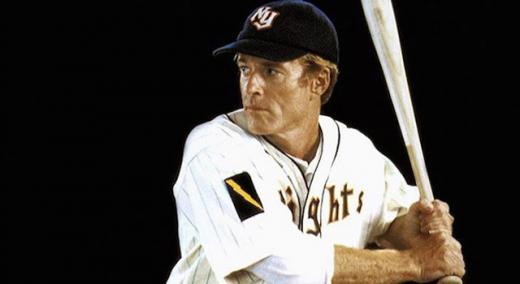

In 1985, about the time I was discovering there was a better way to produce products, The Natural, a film about an aging baseball player with extraordinary talent, was garnering multiple Academy Awards. This archetype concerning natural “God-given” abilities is common in Western culture—in sports and the arts and even in business.

|

ADVERTISEMENT |

Early in my journey as a student of the Toyota Production System (TPS), I observed the same archetype on the factory floor, this time applied to specific lean tools. In a very natural way, certain employees revealed uncanny, focused abilities to reduce waste. Although there was broad interest in continuous improvement, leaders self-selected themselves to excel in specific lean tools.

…

Add new comment