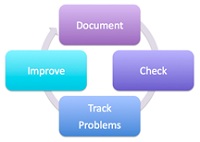

In Part I and Part II of this series we discussed the benefits of using a closed-loop process for managing regulatory compliance called the “circle of compliance,” pictured in figure 1. I also showed how setting up key performance indicators (KPIs) that monitor performance to goals is a good way to check that processes are working properly, thus reducing the need to perform manual audits of a given operation.

|

|

Figure 1: The circle of compliance |

Let’s now take a closer look at the “track problems” step. The primary goal of this step is to collect and analyze data related to operational problems. This is a vital prerequisite for the next step in the process: improve. Remember our overall goal is to systematically and continuously improve regulatory compliance. So let’s first take a look at collecting data.

…

Add new comment