The idea of mixing optics and measurement has its origins hundreds of years ago in the realm of pure science, i.e., astronomy (telescopy) and microscopy. Manufacturing first adopted optics for routine inspection and measurement of machined and molded parts in the 1920s with James Hartness’ development of instruments capable of projecting the magnified silhouette of a workpiece onto a ground glass screen. Hartness, as longtime chairman of the United States’ National Screw-Thread Commission, applied his pet interest in optics to the problem of screw-thread inspection. For many years, the Hartness Screw-Thread Comparator was a profitable product for the Jones and Lamson Machine Company, of which Hartness was president.

|

Horizontal vs. vertical instrument configurations

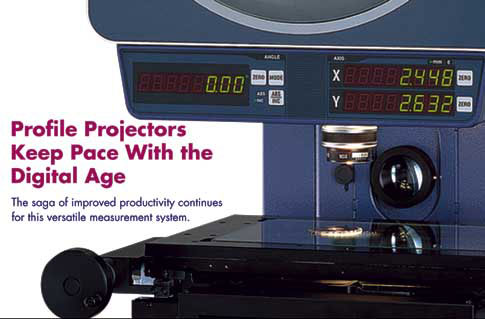

Profile projectors are available in two basic configurations: “horizontal,” where the line of sight of the optical system is horizontal and parallel to the floor, and “vertical,” where the optics looks vertically downward from a position above the workpiece. |

…

Comments

Add new comment