When visually evaluating color, everyone accepts or rejects color matches based on their color-perception skills. In manufacturing, this subjectivity can lead to confusion and frustration between customers, suppliers, vendors, production, and management.

|

ADVERTISEMENT |

This is why color-measurement devices are important in so many industries. By measuring colors using a spectrophotometer, you can communicate and compare spectral data for exact results.

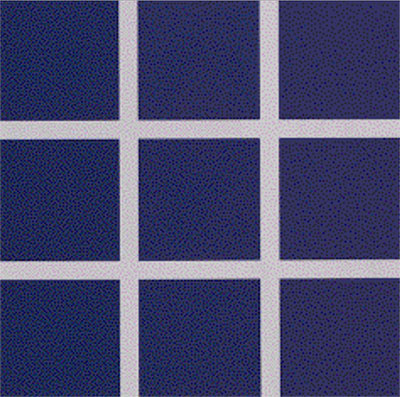

Image 1: Are these acceptable color differences?

To aid in color decisions, color acceptability limits called tolerances can be set as guidelines for how much perceived color difference is acceptable. Tolerances are used to control color, ensure consistency within a production run, and to minimize lot-to-lot variability. But even when using spectral data and tolerances to quantify color, customers and suppliers still find themselves disagreeing.

Why does this happen?

…

Comments

Color should be right the first time

I wasn't aware there are so many different ways of specifying colors. I hope more importers and factories can learn about all these methods so that there's less bickering about color tolerances on orders. It's absolutely an important detail for sure, but I think colors should be the least of someone's quality worries. Thanks for writing this article!

Add new comment