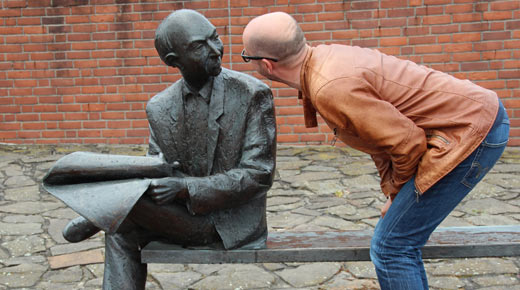

I have a friend. Let’s call him Ryan. I respect Ryan, and we talk about a lot of things: work, religion, technology, politics, bikes, the truck he’s always working on—you name it, and we both have an opinion, sometimes strong opinions. Our problem is, we don’t always speak the same language (well, English, but that’s about it), so sometimes it takes awhile for me to figure out what Ryan is really getting at. And judging from his sometimes dazed expression when I talk, he feels the same.

|

ADVERTISEMENT |

That’s because communication is hard! Really, really hard. But talking—and by that I mean really talking—is how we get stuff done... at work, at home, in our personal lives, and in government. Although we may argue that we do talk, it’s usually along the lines of we said stuff to Bob, and Bob said stuff to us, and maybe we were talking about the same thing, but who the heck knows? We barely remember what he said.

Oddly, we do remember exactly what we said.

…

Comments

A Joy to Read

Thank you, Dirk. This piece was a joy to read. All sensible suggestions. Not easy to put into practice. But, it's just that, it requires practice. I've been practicing, still failing a lot, but have experienced radical change in my interactions and relationships.

Best regards, Shrikant Kalegaonkar (Twitter: @shrikale, LinkedIn, Blog)

Communication????

With apologies to Sir Winston Churchill, "We are organizations divided by a common language!"

...and as that great philosopher Pogo so eloquently noted, "We has met the enemy and he is us!"

When to cede a point

Who's Ryan

The guy who challenges me to think using a different part of my brain. We all need that person who makes us think differently than we normally do. It helps us avoid group think. While it's fun and useful to bounce ideas off people who think the same as you, it's probably more useful, albeit difficult, to force yourself to look at problems from an entirely different perspective. Even if you come away not agreeing, you still come away with knowledge.

One unique aspect of the Quality Digest team, and teams anywhere, is that we all are unique in how we approach problems. From the anal to the ethereal, from the left brain to the right brain (you know who you are) we each contribute a unique perspective to our companies that, when handled correctly, makes those companies stronger.

Add new comment