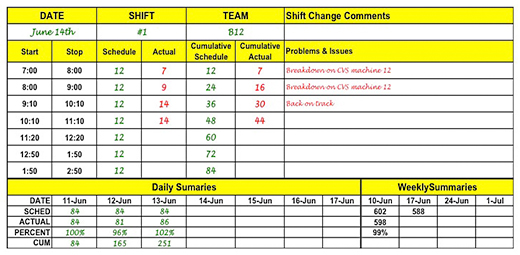

A day-by-the-hour chart helps create control of work processes.

The measurement of people’s efficiency has a long history in manufacturing industries. Design and production engineers calculate the time required to manufacture a product or batch of products. Each time the product is made, the “actual time” is measured and recorded. The efficiency of the production people (or the process) is calculated by dividing the standard time by the actual time.

|

ADVERTISEMENT |

If the actual time is faster than standard, the efficiency will be greater than 100 percent. When the actual time is longer than standard, the efficiency is less than 100 percent.

The purpose of measuring efficiency is to monitor if the people and the process are running at the right speed so that the right number of units are made according to the production schedule, and the needs of the customers. When the efficiency measurement is significantly less than 100 percent, an investigation is made so that the shortfall can be caught up and the reasons for the problem identified.

…

Add new comment