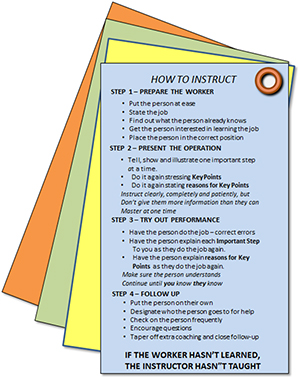

Training Within Industry (TWI) job instruction is built around a four-step process titled “How to Instruct.”

|

ADVERTISEMENT |

Steps two and three are the core of the process:

• Present the operation

• Try out performance

I want to discuss step three: Try out performance

Teaching back as learning

All too often I see “training” that looks like this:

• Bring the team members into a room.

• Read through the new procedure—or maybe even show some PowerPoints of the procedure.

• Have them sign something that says they acknowledge they have been “trained.”

Training Within Industry (TWI) pocket card |

This places the burden of understanding upon the listener.

…

Add new comment