Editor’s note: This story is part of Map to the Middle Class, a Hechinger Report series looking at the good middle-class jobs of the future and how schools are preparing young people for them.

The program had to be a scam. Why would anyone, she wondered, pay her to go to college?

|

ADVERTISEMENT |

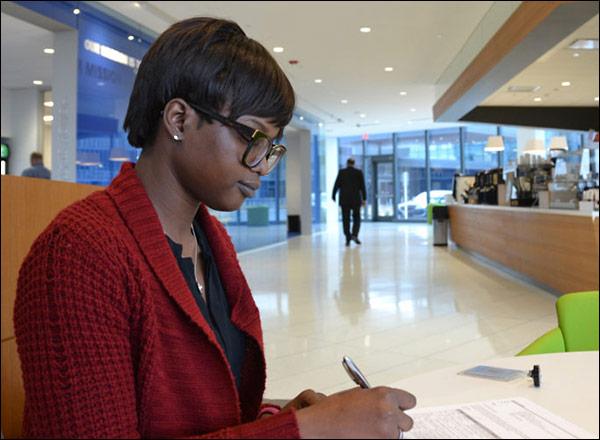

Even after Sarat Atobajeun found information about the program on Harper College’s website, she remained skeptical. A job with a $30,000 salary, plus college tuition and even complimentary textbooks? She called the community college to verify. The Harper receptionist told her it was true: A Swiss-based insurance business with its U.S. headquarters down the street—housed in a behemoth glass building she’d often driven by and puzzled over—had exported its apprenticeship program to the United States.

|

|

…

Add new comment