Body

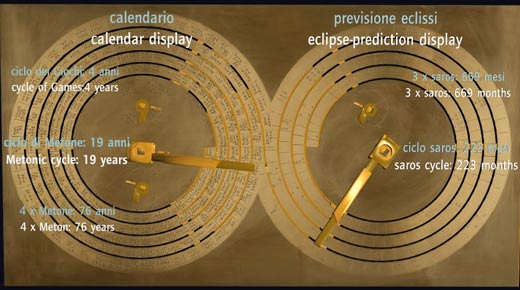

More than 2,000 years ago a huge ship crashed beneath the cliffs of Antikythera, a small island off the coast of Greece. Later discovered in 1900, the wreck yielded a trove of antiquities, including an amazing geared mechanism that, just for starters, predicted eclipses and the location of the sun and moon and possibly planets, showed the phase of the moon, and tracked the four-year cycle of athletic games.

|

ADVERTISEMENT |

…

Want to continue?

Log in or create a FREE account.

By logging in you agree to receive communication from Quality Digest.

Privacy Policy.

Comments

antikythera

There is always the possibilty that this was a "one off" work of an ancient D'Vinci. And let us not forget the knowledge lost with the burning of the Library of Alexandria, or destroyed by zealots.

As for abstract thinking, this is one reason AI will always be limited... the great power of the mind is the ability to imagine and wonder "What if..."

Unfortunately, our educational system (with exceptions) is not geared to be in sync with rapidly changing technology. By the time a technology has reached the textbook, it has matured and taught as "accepted practice". Tomorrow's great ideas are most likely to come from coop students who experience the "real world" and the "hallowed halls" more or less simultaineously.

AI

Hi Alan. The question about AI is interesting. Rather than say more, I heartily recommend you listen to this RadioLab segment.

http://www.radiolab.org/story/137407-talking-to-machines/

Although the first half is interesting, it's the segment that starts 30 minutes into the program that is really, really thought provoking.

At what point does the "A" drop off of "AI"? Can that ever happen? If AI gets sophisticated enough will it be indistinguishable from human thought?

At the root of that question, I think, is the more basic question: are humans just meat computers? Or, is there something in us that comes from "outside" of us.

If so, then the question of whether AI could ever match human thought is probably already answered. If not, if our brains are just very complex chemical computers, and that's it, then couldn't there eventually be a man-made computer that is just as complex as us?

Dilbert Refernce

Nice reference to Dilbert and "Meat Computers."

The ancient Greeks taught the world how to think

The ancient Greeks' stories and achievements essentially taught the world how to think. That is, the Greeks recognized that there was probably a way to do something better, even if humans could currently not conceive of it.

The Antikythera mechanism is particularly impressive because it must have been hand-made, without modern machine tools and without modern metrology methods, but nonetheless performed its intended function

Added abstraction

Thanks Bill.

I think you could point to each of your bullets and draw a direct line from abstract idea to concrete invention. Daedelus is a great example. The idea to be like the gods, or reach for the gods (Babel), or simply the beauty of soaring with the birds eventually led to man being able to fly. A lot of small inventions were needed along the way, but at some point, that abstract idea became a reality.

The Antikythera analog computer

The antikythera mechanism is actually an analog computer of the time. Where to put it in the scale of complexity of instruments of 150 B.C. culture is difficult; perhaps a historian of science can tell us, but I imagine that it is near the best at that time. It seems to be based on the geocentric solar system, and uses fairly basic geometric principles of that time. But its engineering is tremendous. We must be careful to not imbue it with our modern views of its purposes for them. I agree that since astrology was as real to them as automobiles are to us, a timekeeper for olympic events would naturally be folded in with astronomical events.

Progress was made in 1500 years after the antikythera despite the lack of power for devices, in disagreement with Marchant. The astrolabe comes to mind, a cousin of the antikythera. And William Oughtred's slide rule also, after the invention of logarithms by Napier. Both of these are analog computers with no stored potential energy. Machines that use potential energy, i.e., "engines," include the windmill (maybe 9th century A.D.) and the many military machines similar to the trebuchet. Progress would have to be thought of in terms of the mere invention of these devices, for they weren't as sophisticated as the antikythera (the slide rule is the exception).

I agree that invention is the result of application of abstract ideas to the concrete world. In addition to this, "chance favors the prepared mind," as Ben Franklin said. And there is imagination. It took the imagination of Richard Feynman to tell everyone that nanotechnology was possible, decades after the atomic theory of matter was confirmed. But I cannot agree that music and the arts are somehow an essential ingredient to invention. Certainly Einstein was an accomplished violinist, but he never said that this ability was essential for his imagination in physics. It was a soothing avocation for him, period. Science fiction clearly inspires the imagination, but it does not invent anything. Isaac Asimov was an awesome author and popularizer of science, but he did not need his literary expertise in his study of chemistry.

The STEM initiative is so important for the 21st century, but I fear for its dilution when arts get involved as a substitute. I think the STEAM movement is anathema to science and technology (A = arts). I disagree that scientists and artists are more alike than different, as a Scientific American article of some years ago posits. Artists tag along and may make meaningful the advances of science to the common person, but they work with emotions and the common human experience. Neither of these is the coin of the realm for science and technology. In other words, no amount of expertise in Shakespeare could prepare one to construct the Brooklyn Bridge, but enjoying the theatre was probably a nice part of Washington Roebling's life. Chance does not favor the mind prepared with Milton, Chaucer and Dickinson insofar as technological advance is desired.

Thank you for your inspiring column!

Geocentric vs. Heliocentric

Just a note that, if you look at the geocentric mode,l it actually simplified the design and construction of the device... wheels within wheels...

As to the arts being anathema to science, while the arts may not prepare one to build the next great edifice, they will inspire that edifice. Remove the inspiration and there is no need for the engineer, just a super computer to perfectly reduce the requirement to specifications and prints. Perfect function, perfect performance, total lack of elegance...

Importance of STEM

Hi L.F.M.

I agree with you on the importance of STEM. But as I said in the column, I think to eliminate the arts (as is happening in some school districts due to budget constraints) and focus solely on STEM is a mistake. Although I would agree that the arts by themselves probably won't generate a scientific breakthrough, I do believe that the ideas and notions that you find in the arts open the mind to possibilities/connections that might not otherwise come to the inventor. Think of it as using the entire brain instead of only half of it, with one side contributing possibilities to the other.

As far as whether the arts are "essential" to scientific innovation, who knows. I'm not sure it's possible to answer that. I personally think it is, but that is in large part because I have a grounding in both art and engineering, and I know for certain that some of my engineering solutions have come from somewhere other than previous engineering or science teaching or experience.

Thanks for your comments. They did make me stop and think (with both sides of my brain).

Egg or Chicken?

Last night as I considered this discussion, I came to the question, "Which is cause and which is effect?" Is art the catalyst or the byproduct in the process?

Add new comment