| by Dirk Dusharme

You know Six Sigma has reached the mainstream when Forbes magazine awards a “six sigma performance” rating not to a company or individual but to a system of 5,000 self-employed sandwich delivery people--known as dabbawallahs--in and around Mumbai, India. Certainly the dabbawallahs and their practically error-free delivery of 200,000 sandwiches per day is an interesting story in and of itself (read more about it at www.cnn.com/2004/BUSINESS/08/16/mumbai.dabbawallahs). More interesting, though, is the fact that the zero-errors benchmark has moved beyond Six Sigma (with a capital s), a program known mostly to and initiated by corporations, to six sigma (lower case), a synonym for nearly faultless performance.

Although this year’s Six Sigma survey examines the spread of traditional Six Sigma programs in North American companies, keep in mind that, for now at least, Six Sigma is drawing mainstream attention in ways unknown to earlier quality programs.

This year’s results continue to indicate that a lot can be said for the program when it’s properly implemented. As with previous surveys, the vast majority of 2004 respondents claim outstanding results to the bottom line either through waste reduction or increased efficiency.

Our 2004 survey invitation was received by 25,107 quality professionals--Quality Digest subscribers or InsideQuality members. Of those, 1,287 took part in it.

Although small businesses have shown some interest in implementing Six Sigma, it remains a program primarily used by the “Big Boys”--companies with more than 500 employees. However, we’ve recently seen several programs like the one initiated by Mikel Harry that offers Six Sigma online training through the Ira A. Fulton School of Engineering at Arizona State University. Such initiatives are helping small businesses implement Six Sigma. For most of these efforts, the challenge has been to change the program’s deployment model from one that works for large, well-funded corporations to one that adapts to the limited resources of small businesses.

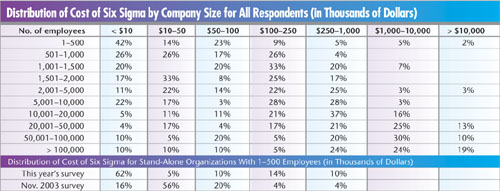

According to our survey, this effort hasn’t paid off yet. This year, only 16 percent of respondents with a Six Sigma program in place came from companies with fewer than 500 employees. (See table below.) About two-thirds of those companies are part of larger organizations and most likely don’t bear the cost of training and implementation on their own--a notorious issue with Six Sigma for small businesses.

In an effort to map perceptions of the cost factor for implementing Six Sigma, we made the following statement in the survey: “Six Sigma costs a lot of money to deploy.” Predictably, those who have a program in place had a much different perception of this than those who don’t. For those respondents who don’t have a Six Sigma program in place and who had an opinion on the statement, 62 percent agreed, with 23 percent strongly agreeing. About 38 percent disagreed. For those who do have a Six Sigma program in place, the numbers were reversed, with 60 percent disagreeing with the statement (11% percent strongly disagreed) and 28 percent agreeing.

The table below shows the breakdown of Six Sigma costs by company size and whether the company is a stand-alone or part of a larger organization. In either case, the majority of respondents with fewer than 500 employees indicate that the total cost of Six Sigma implementation each year is less than $10,000. In the November 2003 survey, the majority of stand-alone companies with fewer than 500 employees reported yearly Six Sigma costs in the $10,000 to $50,000 range. The drop in cost could be due to a difference in how the data were collected or could mean that Six Sigma is becoming less expensive to implement for the small- to medium-size enterprise.

That Six Sigma implementation could cost less than $10,000 per year indicates that these companies probably don’t have full-time Six Sigma employees, the traditional recommendation for implementing the program. Mikel Harry, Thomas Pyzdek and other Six Sigma consultants have previously suggested that the big business approach to Six Sigma could be adapted to small business with Six Sigma-trained personnel using Six Sigma tools as a part of their normal job functions. This, perhaps, is what we’re seeing in smaller organizations.

When the Honeymoon Is Over

The following comments come from survey respondents who are discouraged with Six Sigma and its effects on their companies.

“When senior management isn’t well educated in Six Sigma, the program gets subverted.” “When senior management isn’t well educated in Six Sigma, the program gets subverted.”

“Staff turnover and senior management change can affect the performance of Six Sigma across the company.” “Staff turnover and senior management change can affect the performance of Six Sigma across the company.”

“Excellent tool but management only cares about results. Upper managers say they support it but give little or no resources.” “Excellent tool but management only cares about results. Upper managers say they support it but give little or no resources.”

“Creates an unnecessary empire and removes the focus on business basics in its current form.” “Creates an unnecessary empire and removes the focus on business basics in its current form.”

“Having a basic philosophy of continuous improvement integrated into a company’s culture will take that company much farther than forcing Six Sigma down everyone’s throats.” “Having a basic philosophy of continuous improvement integrated into a company’s culture will take that company much farther than forcing Six Sigma down everyone’s throats.”

“It must be sponsored by someone with authority, or it won’t succeed. Upper-level management support is critical. Resources for regular meetings, data collection, etc., must be committed.” “It must be sponsored by someone with authority, or it won’t succeed. Upper-level management support is critical. Resources for regular meetings, data collection, etc., must be committed.”

“There’s far too much hype associated with Six Sigma. Successful operations should find one operating philosophy, fund it, improve it and stick with it.” “There’s far too much hype associated with Six Sigma. Successful operations should find one operating philosophy, fund it, improve it and stick with it.”

“Six Sigma is another tool for CEOs to reduce personnel to increase profits for their bonuses. The measurement of employee morale doesn’t exist.” “Six Sigma is another tool for CEOs to reduce personnel to increase profits for their bonuses. The measurement of employee morale doesn’t exist.”

“It seems companies train people in Six Sigma yet refuse to implement improvements because of cost, lack of management support, or outright refusal by supervisors to do what’s needed. The Six Sigma process is great, but overall it doesn’t fit the American manufacturing culture.” “It seems companies train people in Six Sigma yet refuse to implement improvements because of cost, lack of management support, or outright refusal by supervisors to do what’s needed. The Six Sigma process is great, but overall it doesn’t fit the American manufacturing culture.”

“The biggest challenge to implementation has been lack of understanding at the upper echelons of the company. Most people in these positions are set in their thinking and have made little effort to learn the concepts. On the other hand, the manager/supervisor/employee level has accepted the methodology with open arms. They note the attitudes of upper management and wonder why it isn’t more supportive. Because this company offers profit sharing, employees see Six Sigma success as money in their pockets.” “The biggest challenge to implementation has been lack of understanding at the upper echelons of the company. Most people in these positions are set in their thinking and have made little effort to learn the concepts. On the other hand, the manager/supervisor/employee level has accepted the methodology with open arms. They note the attitudes of upper management and wonder why it isn’t more supportive. Because this company offers profit sharing, employees see Six Sigma success as money in their pockets.”

“Union leadership reception of Six Sigma/lean is poor, considering the plant has to be profitable to survive.” “Union leadership reception of Six Sigma/lean is poor, considering the plant has to be profitable to survive.”

“Six Sigma shouldn’t be the only methodology; Six Sigma should be used when statistical tools are really necessary. Too often I see projects that could be resolved through a one-week kaizen event, but they’re struggling to make a Six Sigma project out of it. “Six Sigma shouldn’t be the only methodology; Six Sigma should be used when statistical tools are really necessary. Too often I see projects that could be resolved through a one-week kaizen event, but they’re struggling to make a Six Sigma project out of it.

“Top and middle management support is ‘talk’ but not ‘walk.’ It’s expected that Black Belts will ‘just get the job done’ without proper support, involvement and companywide communication on how a project will affect the workforce.” “Top and middle management support is ‘talk’ but not ‘walk.’ It’s expected that Black Belts will ‘just get the job done’ without proper support, involvement and companywide communication on how a project will affect the workforce.”

“Six Sigma is nothing more than a new name for the old yet excellent process improvement methodology based on Dr. Deming’s PDCA. In my humble opinion, it has been repackaged and sold without adding anything substantially new or different (but making numerous consultants and organizations, including publications, very rich in the process).” “Six Sigma is nothing more than a new name for the old yet excellent process improvement methodology based on Dr. Deming’s PDCA. In my humble opinion, it has been repackaged and sold without adding anything substantially new or different (but making numerous consultants and organizations, including publications, very rich in the process).”

“It’s significantly more difficult for a small company to achieve Six Sigma capability and realize improvements due to resource limitations.” “It’s significantly more difficult for a small company to achieve Six Sigma capability and realize improvements due to resource limitations.”

|

Training is a key element for successfully implementing Six Sigma. Nearly 22 percent of respondents with Six Sigma programs report that all employees are required to take Six Sigma training.

The amount of training time is also important. The table below shows how much time companies invest in Green and Black Belt training. For Green Belt training, the majority (58%) of companies require a week or more of training, with about 23 percent requiring more than two weeks. Black Belts require three times that amount of training. The majority (63%) of companies require three to five weeks of Black Belt training, and 20 percent require more than five weeks.

2004 shows a continuation of the trend for companies to abandon Six Sigma at about year three or four. (See table below.) There are several reasons for this. The most likely is that Six Sigma, in practice, is really no different than other quality programs. If it shows tangible results, companies continue to use it until they reap the immediate benefits. At that point, the major cost savings due to reduced waste have been realized. If Six Sigma efforts haven’t been expanded to include the product-design function, then companies most likely will abandon the program.

A comment that recurs every time we run this survey is that Six Sigma reaps benefits not so much because of its methodology but because it’s new, exciting and gets everyone to at least temporarily focus on their companies’ processes--always a good thing.

Mikel Harry suggested another scenario in an interview last year: Six Sigma has become “institutionalized,” i.e., it’s simply the way companies do business, even if those organizations don’t refer to the process as “Six Sigma.” Comments on the survey lend some support to Harry’s argument. Many companies still call their programs “TQM” and argue that it’s no different than Six Sigma.

A factor contributing to attrition could be loss of management support. Six Sigma gurus have always stressed that unless Six Sigma becomes a part of a company’s culture, the program will falter. The implication is that managers come and go, but the company lives on. If Six Sigma--or TQM, or Quality One, or We Be Quality--is a manager’s pet project rather than a culture-driven initiative, it will last only as long as the manager or the manager’s attention span. At that point, it’s on to the next big thing--or nothing at all.

In general, respondents report that implementing Six Sigma programs has had a positive effect on their companies and businesses, although these numbers have declined a bit from last year.

When it comes to job satisfaction, about 44 percent of respondents report that job satisfaction has improved since Six Sigma was initiated in their companies, down from last year’s 53 percent. About 62 percent indicate that company profitability has increased as a result of their program, down from 73 percent last year. Customer satisfaction was the only metric of note that improved. Nearly 58 percent of respondents indicated that customer satisfaction has improved as a result of Six Sigma, up from 54 percent in last year’s survey.

In the past, we’ve printed examples of the results that companies have gleaned from their Six Sigma programs. (See last year’s survey results at www.qualitydigest.com/nov03/articles/01_article.shtml.) There’s no doubt that a properly implemented Six Sigma program positively affects a company’s bottom line and offers potentially huge savings in production costs. This year’s survey shows the same types of dollar and resource savings, so rather than repeat information similar to last year’s survey, we took a look at the negative side of Six Sigma implementation, according to 10 percent of our respondents. By doing so, we don’t intend to criticize the program but rather to suggest some possible answers to those who wonder why their quality programs are faltering.

Among the biggest complaints is that, while it seems like a potentially good program, Six Sigma suffers at the respondents’ companies because of lack of management support, lack of management understanding, lack of resources, unreasonable expectations and a misunderstanding of what Six Sigma actually is. (See the sidebar, above right, for a sampling of why the program is failing at those companies.)

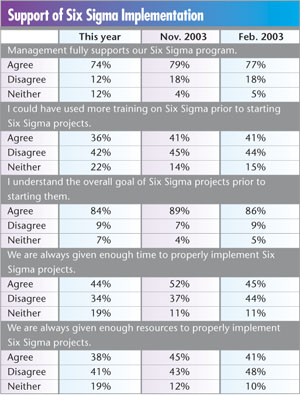

Those comments aside, most respondents feel the program is well-supported at their companies. About three-quarters (74%) of respondents agreed with the statement, “Management fully supports our Six Sigma program,” with 33 percent agreeing strongly. (See table below.)

However, when it comes to training, time and resources, the story strays somewhat from this rosy picture. About 36 percent of respondents indicated that they could have used more training prior to starting Six Sigma projects, with 42 percent indicating that training wasn’t a problem. Nearly one-third of respondents indicated that they weren’t given enough time to properly implement Six Sigma projects, with 44 percent indicating that time wasn’t an issue. About 41 percent of respondents indicated that they weren’t given the resources necessary to properly implement Six Sigma projects, and about 38 percent indicated that this wasn’t a problem.

While these types of Six Sigma surveys attempt to assess the impact and spread of traditional Six Sigma programs within a corporate setting, the true measure of a movement is its presence in mainstream society. We’ve looked at how companies such as Motorola Inc., Honeywell, Praxis, TRW and numerous small companies use or try to use Six Sigma as the means to an end--i.e., improved profits. The real story might be that six sigma, that versatile, lower-case phenomenon, is at work in more unusual settings--like India’s dabbawallah industry.

Dirk Dusharme is Quality Digest’s editor in chief.

|