by Laura Smith

There's no question that the application of quality methodologies will benefit the pharmaceutical and medical device industries. But why has it taken these successful, politically powerful and extraordinarily wealthy industries so long to recognize quality's value? How have they been so successful for so long without the widespread use of the quality programs that are almost universally adhered to by their manufacturing counterparts in every other industry on the planet?

There are many answers to those questions. When considering compliance to medical device and pharmaceutical regulations, it's important to remember that although Big Pharma, defined as the top 20 pharmaceutical companies, hasn't historically used quality techniques such as Six Sigma, the industry--and by extension, the also-heavily regulated medical device industry--has been forced to comply with stringent quality control requirements. The Food and Drug Administration requires that these companies submit to regular on-site inspections and product monitoring, and that they reveal the methods used in clinical trials proving drug efficacy. In effect, the FDA has served as a kind of quality control agency for pharmaceutical and medical device companies.

But that reputation for ensuring the quality of pharmaceuticals and protecting the public has taken a beating in recent years, especially with recent high-profile consumer problems and lawsuits. Merck & Co. Inc., the second-largest drugmaker in the United States, is facing almost 10,000 lawsuits stemming from consumers who were injured or sickened by its drug, Vioxx. The company states that it has $685 million set aside to cover expected consumer damage awards and legal costs. As a result of this and similar cases, the FDA and Congress have taken a stricter approach to drug approvals, requiring longer drug trials and voluminous data to prove a drug's safety and efficacy. All of this costs money--and a lot of it.

The added costs for drug approval on the back end of the process has forced drug companies to look to the front end to save money. It's something they've never had to do before, but Big Pharma is looking to popular quality methodologies to save money and cure itself of the dreaded "Bigspenderitis" disease.

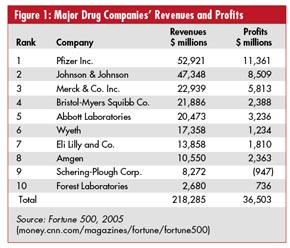

In a nutshell, Big Pharma never worried about cutting costs and improving efficiencies because the industry didn't have to. The cost-containment and process-improvement obsession of the rest of the manufacturing world was never a worry for the pharmaceutical industry, simply because it was too wealthy to worry about it. Figure 1 provides a graphical description of major drug companies' revenues and profits for one given year (2005).

Instead of cost restraints and improved efficiencies, the focus of pharma companies has always been on The Next Big Thing. It was only five years ago that pharma companies even started to become interested in managing front-end costs through methodologies like lean and Six Sigma.

"[Lean and Six Sigma] were never on pharma companies' radar until then," says Gary Tyson, clinical development practice vice president at Campbell Alliance, a consultancy specializing in the pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries. "Costs weren't the concern. The focus has always been on getting the product out to the market the fastest. That's what everyone has wanted to do, and that focus has made these companies very successful."

That get-it-approved-first mentality is still paramount to the pharma industry, but the need to cut costs is becoming increasingly important. For one, the cost of developing new drugs has never been higher. According to the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America ( Phrma), the average cost for developing a single new drug is $802 million. In comparison, that average cost was a relatively paltry $138 million in 1975. Tufts University recently released a study that revealed that the costs are skyrocketing mainly because of the high number of failures early in the process; many of them are identified by the FDA's

Byzantine--yet important--approval processes. Just one in 5,000 screened drugs makes it to the market as a new medicine, and even that doesn't guarantee its maker a profit. PhRMA reports that only three out of 10 marketed drugs produce enough money to pay back or exceed its development costs. Furthermore, it takes 10 to 15 years to shepherd a new drug from the laboratory through the FDA's regulatory-approval process.

To pay the big bills required by the approval process, Big Pharma has to bring in big bucks. Even with tighter FDA restrictions and bigger overhead costs, Big Pharma equals big money. Pharmaceutical industry profits have dwarfed those of every other major industry in recent years: In 2005, the industry raked in more than $36.5 billion in profits. That's five-and-a-half times larger than the median for all industries represented in the Fortune 500, according to Public Citizen, a nonprofit consumer advocacy organization. For example, Pfizer, the world's largest drug company, reported a profit of $11.3 billion out of sales of almost $52 billion in 2004.

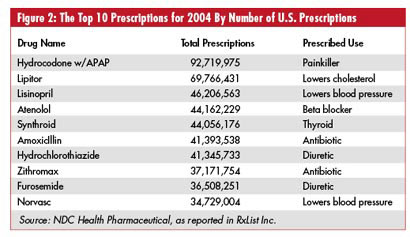

No one is saying that Big Pharma is going broke--quite the opposite. But there are hints that the industry's massive profit margins are entering a period of sustained shrinkage, and this has executives looking for ways to cut overhead costs and reroute that money into getting new, patented drugs to the market. Three of the most-prescribed drugs in the world--Pfizer's extremely lucrative Zoloft antidepressant, along with Merck's Zocor and Bristol-Myers Squibb Co.'s Pravachol, both of which lower cholesterol, will likely lose their patent protections this year. Experts forecast that this will remove about $12 billion of the U.S. market for branded prescription drugs as consumers switch to cheaper generic equivalents. The new Medicare prescription drug plan heavily favors generic drugs, too, a fact that has industry analysts forecasting significantly reduced demand for the more lucrative branded drugs. New "me-too" drugs--those that are similar to existing pharmaceuticals--entering the market this year will also erode profits.

Additionally, some industry analysts report that the pharmaceutical industry is undergoing fundamental changes. Advances in genomics and individualized medicines will make it much harder for pharmaceutical companies to count on developing "blockbuster" drugs that foot the bill for dozens of less-lucrative and/or failed drugs. All of this forces drug companies to become more efficient if they are to continue to thrive in an increasingly competitive market.

Innovative companies such as Nektar Therapuetics--which is developing Exubera, a much-anticipated inhaled form of insulin for diabetes patients--have realized that the goals of Six Sigma and the FDA are very similar: variability reduction.

That capability has broad implications for the pharma industry, says Robert Blaha, Human Capital Associates president. His firm specializes in business transformation through lean and Six Sigma, and Blaha consulted with Glaxo on its lean Six Sigma operations before it merged with SmithKline. Implementing Six Sigma in pharma companies has problems specific to the industry, states Blaha--namely, that an emphasis on process efficiencies is so new to most upper-level pharma executives that it's "almost a foreign language" to them.

"Most leaders in pharma companies came up in a time of huge profit margins, when they could operate seven manufacturing plants when they only really needed two, and when they could afford to have several hundred more employees than they really needed," Blaha says. "… are sort of a shot right across the bow to them. They're having to learn a whole new way of doing business."

Because management buy-in and central leadership are paramount in the success of any lean or Six Sigma effort, immersing pharma executives in the methodologies is especially important. "For Six Sigma to be successful, it can't be about what a leader says; it has to be about how he thinks, how he acts, what questions he asks and about the way he runs the business," says Blaha. "That's a difficult thing to teach in a seminar or two."

Blaha observes that several pharma companies are leading the way in what is likely to be the "new normal" for the pharma industry. GlaxoSmithKline, which has implemented Six Sigma across its worldwide operational divisions, "gets it," according to Blaha. So does Tim Tyson, president and CEO of Valeant Pharmaceuticals. Tyson has attended several of Blaha's Six Sigma workshops and seminars. Tyson's faith in Six Sigma shows in Valeant: The company has implemented an organizationwide Six Sigma effort that extends to all parts of the business.

Valeant reports that it saved $10 million in its first full year of practicing lean Six Sigma, a figure that includes deep staff reductions in almost two dozen of its worldwide manufacturing plants. The company has reduced its manufacturing staffing levels from almost 12,000 to just over 3,800, and its number of plants from 33 to just eight. The company reports that it plans to further reduce its manufacturing staff this year, when it closes facilities in Montreal and Brazil. Overall staffing levels are expected to remain steady, though, as the company hires additional sales representatives. All of this--fewer manufacturing personnel, but additional sales reps--is a testament to the remarkable efficiencies Valeant has made.

At this early point in the methodologies' histories within the pharmaceutical industry, lean and Six Sigma have mainly been used in companies' administrative, marketing and distribution functions. Research and development has been a tougher nut to crack, because that function tends to be necessarily more fluid and creative.

"If there is not enough data to measure--and sometimes there isn't if, in the case of R&D, there was only a small amount of data captured--Six Sigma isn't as applicable," says Tyson. "There need to be measurable trends for it to be useful information."

According to MedAd News, Merck has applied Six Sigma to its sales function in an effort to reduce the number of sales representatives promoting the same drug. Eli Lilly, the twelfth-largest pharmaceutical company in the world, estimates that it will realize a $250 million benefit from its approximately 160 Six Sigma projects.

There's more to managing quality and improving processes than Six Sigma and lean. ISO 13485,which applies to medical device and pharmaceutical companies,requires a stringent examination of a company's risk management procedures. The standard was revised in 2003, in part to "make the resulting text consistent with the objective of reflecting the current regulations and facilitating the harmonization of new medical device regulations around the world," as the standard reads. In effect, this requires a shift to a process-based approach to inspection and, eventually, product approval--hallmarks of the ISO 9001 standard on which ISO 13485 is based.

The FDA seems to be moving toward harmonizing its own regulations with those of the rest of the world. Its Quality System Inspectional Technique, which applies to medical devices, is a process-based approach that allows inspectors to examine management systems, corrective and preventive actions, documented and validated procedures, paper trails and device history records to ascertain a manufacturer's quality management system for a particular product. This new globally harmonized approach means that the FDA might eventually recognize ISO 13485 registration as partial evidence of regulatory compliance--an approach that is already evolving in Canada and Europe.

The FDA is also cooperating with two international efforts that apply to the medical device and pharmaceutical industries: the Global Harmonization Task Force, which applies to medical devices, and the International Conference on Harmonization of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH).

Although there's been plenty of interest in process improvement in the pharma industry in recent years, the methodology's history with the industry is still very new. Profit margins have declined in recent years, but they're still much larger than in other industries, a sign that the industry could still slip in its newfound dedication to urgent cost-reduction methodologies. Whether the industry is serious about quality is still unclear, though there have been early signs that a few companies can take the lead and show their competitors how to trim the proverbial fat and succeed in a new pharmaceutical market.

Laura Smith is Quality Digest's assistant editor.

|