Baselines for Change

We're often told that change is the only constant in our world, and much of the time life seems to prove that notion to be true.

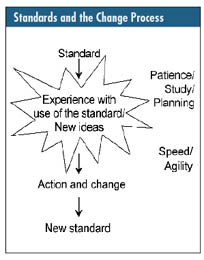

On the other hand, we find ourselves constantly needing to conform to standards. What, then, is a standard's true role? Normally, standards follow development. They seldom lead it. They're created when a technology, idea or process has matured to the point where it's feasible to describe it in words that can be broadly agreed upon among a common group of users. Standards serve as baselines to determine conformity with generally accepted practices. But they can also become a baseline for improvement.

Writing a standard on any topic requires a great deal of effort. First, the topic must be fully explored and understood. Then the standard must be drafted and, finally, consensus must be reached among the users. By the end of this development process, the standards writers have learned a great deal. By describing what we've learned in the standard, we provide a baseline that everyone can use to make improvements. Thus, developing a standard implies creating a baseline for change.

Standards are sometimes considered nothing more than documents to which compliance is required. Perhaps this is due to the nature of problems. When a problem occurs, there are three potential causes that relate to standards: Either no standard existed, the existing standard was inadequate or the existing standard wasn't followed. The solution to the problem will then require creating, modifying or enforcing the standard. Even in these simple cases, standards are used as the basis for organizational improvement and change. Standards are sometimes considered nothing more than documents to which compliance is required. Perhaps this is due to the nature of problems. When a problem occurs, there are three potential causes that relate to standards: Either no standard existed, the existing standard was inadequate or the existing standard wasn't followed. The solution to the problem will then require creating, modifying or enforcing the standard. Even in these simple cases, standards are used as the basis for organizational improvement and change.

But there's much more to a standard than issues of conformity. As experience is gained from using a standard, it's useful to gather feedback on how well the standard meets user needs. It's necessary to study the feedback to understand its significance. We must look for signs that change would be beneficial. We must learn what new ideas affect the standard and determine which of them should be incorporated.

It's also necessary to wait for the right time to incorporate these changes and ideas. Even in this era of rapid changes, new ideas are often rejected in the marketplace because the timing of their introduction isn't favorable.

Planning is required to achieve successful change. We've all seen cases where the first producer to bring a new idea to market failed while a competitor with better (i.e., later) timing was wildly successful with the same idea. The first competitor succeeded in setting the new standard, but the second made all the money.

Once the timing is right, it's important to act quickly. Often the period of study, waiting and planning requires years, but when it's time to act, speed and agility are almost always critical to success.

These ideas apply to many types of standards, including performance, product and testing standards, among others. They even apply to management systems standards such as ISO 9001, where the quality management system provides an expectation of, and baseline for, improvement. Its proper implementation provides an organization with the tools to maintain the gains made through improvement efforts, including initiatives such as lean manufacturing and Six Sigma.

We all know that, in many cases, just following standards isn't enough. Rather, it's often necessary to go beyond their requirements or suggestions to achieve value for our customers and other stakeholders. It's not often that I hear people talking about the work required to create new standards or modify old ones.

John E. (Jack) West is a consultant, business advisor and author with more than 30 years of experience in a wide variety of industries. From 1997 through 2005 he was chair of the U.S. TAG to ISO TC 176 and lead delegate for the United States to the International Organization for Standardization committee responsible for the ISO 9000 series of quality management standards. He remains active in TC 176 and is chair of the ASQ Standards Group

|