| by Stanley H. Salot Jr.

If you've been selling electrical products to Europe, you already know about that continent's directives regarding Restriction of Hazardous Substances (RoHS) or Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment (WEEE) that limit that amount of certain heavy metals and other hazardous substances contained in products or waste.

The near prohibition of lead, mercury, cadmium and hexavalent chromium, all largely used in electronic or electrical products, as well as polybrominated biphenyls and polybrominated diphenyl ethers used as flame retardants in plastics and fabric coatings, has led many manufacturers to revamp their processes and supply chains to meet the directives.

To meet compliance criteria for RoHS, WEEE and other green initiatives, some companies have turned to ISO 14001. But is that the right route to take?

The path a company must take to demonstrate that its electrical and electronic products are hazardous-substance-free (HSF) is anything but easy. It must provide more than a self-declaration of conformance to demonstrate due diligence, but this process can't be so onerous that it puts the company out of business. Some people believe that ISO 14001 is well-suited for demonstrating an organization's compliance with HSF requirements, but many others say it's not the right tool for the job. I certainly fall into the latter group.

ISO 14001 was designed to address management of the environmental issues and effects that a company might have on the world at large. The standard's introduction states that it is "… intended to apply to all types and sizes of organization and to accommodate diverse geographical, cultural and social conditions." This language was necessary to provide a very broad range of requirements with a great deal of flexibility. Such flexibility is a positive attribute of ISO 14001 for environmental management but a negative one for addressing the technical requirements of hazardous-substance management in products and the processes that build them. As written, ISO 14001 doesn't directly address the technical requirements of product design or the materials used in the product. The standard's scope statement makes the following qualification: "It applies to those environmental aspects that the organization identifies as those which it can control and those which it can influence. It does not itself state specific environmental performance criteria."

This language in the standard's introduction and scope offers perhaps the most telling reason why it would be inappropriate to use ISO 14001 as the certification tool for demonstrating compliance with Europe's RoHS or WEEE directives and other green manufacturing processes. As a producer of consumer products that must also have the potential to demonstrate due diligence in a court of law, I couldn't be assured by an ISO 14001 international certification that my supplier was meeting my requirements without performing second-party assessments.

You have only to look at RoHS to see that it specifically addresses the technical aspects of a company's product. It requires a company's marketing and sales functions to have a detailed understanding of their customer requirements. It also requires a company's engineering team to understand all the materials used to make the products and to replace components that don't support the directive's requirements. To ensure compliance, the directive places supply chain management responsibility for compliance on the producer of the consumer product. A producer must determine its supplier's competence and compliance to the RoHS directive at a technical level. RoHS also requires suppliers to demonstrate that they have a vigilant system in place for notification should their compliance fail for any reason.

Once their supply chain management systems are under control, producers must address their own internal manufacturing systems. These must be capable of demonstrating the same level of competence, compliance and process controls to ensure that no hazardous substances get into the system. Producers must also ensure that they have product-lot control to address potential problems. They must have a vigilant preventive-action system in place in case their compliance fails for any reason.

Research undertaken by The Salot Bradley Group International (SBGi) during the past 18 months clearly indicates that major corporations worldwide are investing millions of dollars testing products and components, building supply chain management systems and generating thousands of pages of questionable test records, all to support the potential need to demonstrate their due diligence.

What we've learned from analyzing ISO 9001 and ISO 14001 is that neither of these international standards specifically addresses the technical requirements necessary to ensure that a company has the systems in place to demonstrate due diligence, should a hazardous-substance restriction issue arise that results in legal action.

We've also learned from experience that smaller companies that have tried to use ISO 14001 to demonstrate RoHS compliance have run up against the broader scope of the standard and found the task a great deal more difficult. This activity often takes primary focus away from RoHS compliance and places it on the broader aspects of ISO 14001. A substantial burden is placed on smaller suppliers and often results in long delays in demonstrating compliance. Consequently, producers must continue to test incoming products and perform second-party assessments.

Compliance to the RoHS directive, including the ability to demonstrate due diligence, requires highly focused technical skills in the following areas:

•Contract review

•Design control

•Procurement

•Supply chain management

•Materials management

•Production control

•Infrastructure

These technical skills are varied, but all have one element in common: Individuals must be qualified to carry out the specific tasks associated with managing the hazardous substances used in products or in their manufacturing process.

ISO 14001 doesn't specifically address the information necessary to demonstrate due diligence in the following key areas:

•Contract review

•Design control

•Procurement

•Supply chain management

•Infrastructure

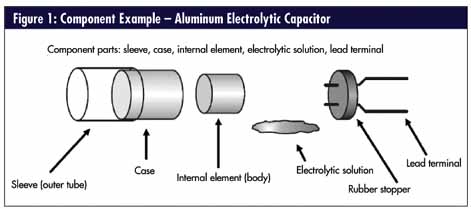

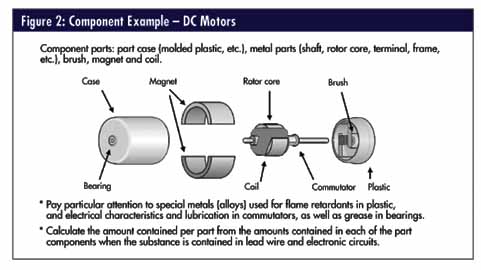

To illustrate the point, figures 1 and 2, taken from the survey and response manual of the Japan Green Procurement Survey Standardization Initiative, demonstrate the technical aspects of two types of components that must be analyzed and controlled to demonstrate due diligence. In both of these examples, it is up to the company's engineering team to understand the makeup of every component and whether it meets a directive's requirements.

Although anything is possible, in my opinion you can't show compliance to green manufacturing initiatives with ISO 14001. Using ISO 14001 as the means of demonstrating compliance to RoHS, WEEE, various Green Partner programs and the soon-to-be-released administrative measure China MII No. 39 will still require producers to perform second-party assessments to ensure their ability to demonstrate due diligence. ISO 14001 doesn't address these technical requirements and thus doesn't provide the basis for the substantive hazardous-substance restriction assessment needed to meet the new requirements and accountabilities currently imposed.

If industry thought ISO 14001 would fit the need, why did virtually every major original equipment manufacturer (OEM) in the world create its own Green Partner program, develop specific testing criteria for products and components, and hire thousands of supply chain management assessors? Why did every product testing facility in the world spend millions, if not billions, of dollars hiring additional staff, expanding and/or building new facilities and creating its own unique certification schemes?

It wasn't hard to recognize the need for a technical solution to a technical problem at the international level. This issue was first brought to the attention of the U.S. National Authorized Institute (U.S. NAI) for the International Electrotechnical Commission Quality Assessment system by an Asia-Pacific manufacturers association.

After extensive research with producers, testing facilities and legal counsel worldwide, the requirements of the European RoHS and WEEE directives, as well as those identified in many OEM Green Partner programs, were brought together in the U.S. standard EIA/ECCB-954. Following a successful pilot program managed by the U.S. NAI for the IECQ, this U.S. standard was adopted by the IECQ and is now known as the QC 080000 Electrical and Electronic Components and Products Hazardous Substance Process Management System Requirements (HSPM) specification. Unlike ISO 14001, QC 080000 IECQ HSPM specifically addresses the requirements for demonstrating compliance with the restriction of hazardous substances used to produce components and products, and for green process manufacturing.

QC 080000 IECQ HSPM's introduction clearly states its applicability to the HSF requirements facing industries today: "This IECQ specification and its requirements are based on the belief that the achievement of HSF products and production processes cannot be realized without an effective integration of management disciplines. This specification is a supplement to, and exists in concert with, the ISO 9001 QMS framework for the comprehensive, systematic, and transparent management and control of processes pursuant to HSF goals. This document is based on the EIA/ECCB-954 Electrical and Electronic Components and Products Hazardous Substance Free Standard and Requirements to serve as guidance for manufacturers in the fulfillment of HSF and customer requirements which may include regulatory requirements such as Directive 2002/95/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 January 2003 on the restriction of the use of certain hazardous substances in electrical and electronic equipment (RoHS), and Directive 2002/96/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 January 2003 on waste electrical and electronic equipment (WEEE)."

As of this writing, the QC 080000 IECQ HSPM has been translated from English into French, Chinese, Korean and Japanese. It's under consideration for adoption as a national standard in many of these language's corresponding nations.

Certification services are being offered by many of the most prestigious registrars in the world: NSAI, DNV, LCIE, LCIE/BV, SGS, CEPREI, Intertek, TÜV-SÜD, UL, GCS, and BSI.

Approximately 75 companies have been assessed to QC 080000 IECQ HSPM worldwide. Approximately 200 more are expected to achieve certification before the end of 2006. Estimates are for more than 500 to seek certification in 2007.

Although I'm admittedly a bit biased, I can't help but believe that QC 080000 IECQ HSPM is the right tool at the right time for the right reason.

Stanley H. Salot Jr. is a founder and chief technology officer of The Salot Bradley Group International (SBGi) and serves on its board of directors. He serves as president of the Electronic Component Certification Corp., the U.S. representative of the International Electrotechnical Commission Quality Assessment System for Electronic Components, and is a board member for the Electronic Component Certification Board. Salot co-authored the international standard QC 080000 IECQ HSPM for hazardous-substance process management for the electronics and electrical industries.

|