| by Roderick A. Munro, Ph.D., and Ronald

J. Bowen

Have you noticed the recent

news about the automotive industry? Industry gossips hint

that U.S. automakers aren’t happy with supplier performance

under the QS-9000 requirement and consider ISO/TS 16949:2002

a last chance for the international community to prove its

ability to ensure “perfect parts.” Consider:

Toyota has enough cash to buy both Ford Motor Co. and General

Motors Corp. if it wanted--but why would it?

Toyota has enough cash to buy both Ford Motor Co. and General

Motors Corp. if it wanted--but why would it?

Toyota is developing a new vehicle line--Scion--aimed at

young buyers. (People laughed when it developed Lexus, too.)

Toyota is developing a new vehicle line--Scion--aimed at

young buyers. (People laughed when it developed Lexus, too.)

GM and Ford have made tremendous quality improvements during

the last 20 years, but in some key areas they haven’t

kept pace with Japanese automakers.

GM and Ford have made tremendous quality improvements during

the last 20 years, but in some key areas they haven’t

kept pace with Japanese automakers.

During the 1980s, U.S. OEMs were concerned about supply-base

reductions for a number of reasons, notably eliminating

poor performance. Now OEMs want to raise the bar even higher.

Who will be left? Only “excellent” suppliers?

What will it take to become an excellent supplier in the

automotive community? How will suppliers deliver only perfect

parts?

Both Ford and GM are closing the gap between them and

Toyota and are working with suppliers to ensure that parts

delivered to automakers’ assembly plants are the best

they can be. This article takes a look at a few efforts

that are currently underway.

The industry uses something called automotive core tools

to establish processes that meet customer requirements.

The five basic tools include:

Advanced product quality planning and control plans. These

are developed by product engineers rather than quality engineers.

The process monitors planning procedures during the design

and development of assembly plant products and establishes

controls to ensure perfect parts.

Advanced product quality planning and control plans. These

are developed by product engineers rather than quality engineers.

The process monitors planning procedures during the design

and development of assembly plant products and establishes

controls to ensure perfect parts.

Production part approval process. This is carried out by

the supplier before production to ensure that everything

is ready. Thus, the run-at rate must be achieved before

the OEM assembly plant is ready to launch.

Production part approval process. This is carried out by

the supplier before production to ensure that everything

is ready. Thus, the run-at rate must be achieved before

the OEM assembly plant is ready to launch.

Failure mode and effects analysis. This is conducted in

both design and potential production failure modes to anticipate

problems and ascertain their risks prior to any occurrences.

Failure mode and effects analysis. This is conducted in

both design and potential production failure modes to anticipate

problems and ascertain their risks prior to any occurrences.

Preventive action is carried out to eliminate the problems.

Statistical process control. This reduces variation in the

process and monitors process behavior characteristics. Under

the international standard, all employees are required to

know how to analyze statistical data. Using all the basic

statistical tools--not just control charts--is key.

Statistical process control. This reduces variation in the

process and monitors process behavior characteristics. Under

the international standard, all employees are required to

know how to analyze statistical data. Using all the basic

statistical tools--not just control charts--is key.

Measurement systems analysis. It’s more important

than ever for a supplier to be aware of a measurement system’s

uncertainties in order to establish benchmark data about

ongoing improvements. A single gage repeatability and reproducibility

study will no longer suffice. At least for families of gages,

suppliers must conduct stability, bias, linearity and graphical

analysis studies in conjunction with the gage R&R analysis.

Measurement systems analysis. It’s more important

than ever for a supplier to be aware of a measurement system’s

uncertainties in order to establish benchmark data about

ongoing improvements. A single gage repeatability and reproducibility

study will no longer suffice. At least for families of gages,

suppliers must conduct stability, bias, linearity and graphical

analysis studies in conjunction with the gage R&R analysis.

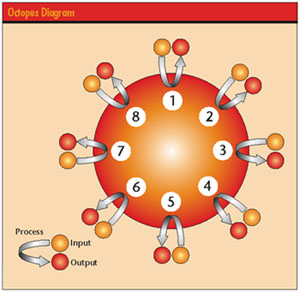

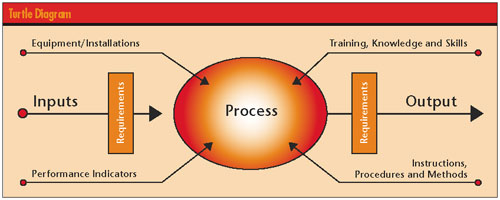

Along with these five basic tools, additional methods

are now in use. ISO/TS 16949:2002’s new process approach

emphasizes process auditing, and internal auditors are expected

to identify turtle and octopus diagrams that lead to preventive

action reports, as illustrated on pages 60 and 62. This

approach should produce many more PARs than the traditional

corrective action report method. If all process activities

are correct and flawlessly executed, outputs will likewise

be flawless.

Six Sigma initiatives have been established. Specially

trained individuals and teams identify variation reduction

opportunities and process improvements. Both Ford and GM

now require suppliers not only to use problem-solving tools

but anticipate quality improvements of both parts and services

that are delivered to OEMs.

Is GM returning to the days of the conglomerates, fully

supported by Wall Street? The stage was set even before

the “bubble,” those stock market excesses created

by momentum players and traders.

GM’s pilot programs, Yellowstone and Blue Macaw,

might give us a glimpse into the future. Blue Macaw is GM’s

small-car program in Brazil, where it builds the Chevrolet

Celta. Lear is only one of its just-in-time suppliers. In

2000, Lear built a 63,000 ft2 facility adjacent to GM’s

Gravatai Automotive Complex so that car seats could be installed

immediately into the Celta.

Yellowstone is the code name for GM’s North American

Car Group’s plan to achieve profitability. “Yellowstone

builds on Blue Macaw and tailors the concepts to North America,”

explains GM’s Bill Hogan. The Yellowstone concept

includes codesigning with suppliers as well as modularity,

the latter being defined as combining subsystem components

into a single assembly-part number for delivery to the plant.

With codesigning, GM and its supply base work together to

define module requirements. Suppliers are far more involved

in product development than ever before.

Since 1999, GM has replicated these two pilots and the

lessons learned. In a September 2000 article in Automotive

Industries, John McCormick wrote: “GM’s new

plant in Thailand is cranking out Opel Zafires--and setting

the stage for other ‘common footprint’ plants

to come. In the pipeline for the next two to five years

are new Delta Township and Lansing Grand River plants in

Michigan, as well as a massive investment in a fresh facility

at Opel’s mammoth Russelsheim, Germany, complex. All

of these and more to follow will benefit from the lessons

learned in Rayong, Thailand, and its three sister plants

in Poland (Gliwice), China (Shanghai) and Argentina (Rosarlo).”

For more information, read the following articles regarding

Yellowstone and Blue Macaw:

“Yellowstone Provides Basis for Profitability in Small

Cars, GM’s Hogan Tells World Congress,” PR Newswire,

Jan., 1999 (www.findarticles.com/cf_0/m4PRN/1999_Jan_11/53545441/print.jhtml)

“Yellowstone Provides Basis for Profitability in Small

Cars, GM’s Hogan Tells World Congress,” PR Newswire,

Jan., 1999 (www.findarticles.com/cf_0/m4PRN/1999_Jan_11/53545441/print.jhtml)

“Another Piece of the Puzzle (General Motors’

new Thailand plant),” Automotive Industries, Sept.,

2000 (www.findarticles.com/cf_0/m3012/9_180/65352732/print.jhtml)

“Another Piece of the Puzzle (General Motors’

new Thailand plant),” Automotive Industries, Sept.,

2000 (www.findarticles.com/cf_0/m3012/9_180/65352732/print.jhtml)

“Lear Corporation Inaugurates New Brazilian Plant

to Supply General Motors Corp.’s Gravatai Automotive

Complex,” PR Newswire, July, 2000 (www.findarticles.com/cf_0/m4PRN/2000_July_20/63573448/p1/article.jhtml)

“Lear Corporation Inaugurates New Brazilian Plant

to Supply General Motors Corp.’s Gravatai Automotive

Complex,” PR Newswire, July, 2000 (www.findarticles.com/cf_0/m4PRN/2000_July_20/63573448/p1/article.jhtml)

GM’s strategy appears to be right on track. Lansing

Grand River is in place, and suppliers now build and install

the front-end module right on line. Given this, it’s

easy to imagine suppliers staffing future assembly centers.

Each step of the process, from the body shop through car

track and shipping, would be the supplier’s and its

organization’s responsibility--consequently requiring

that suppliers be registered to ISO/TS 16949:2002 and

comply with the GM site’s ISO 14001 EMS processes

and procedures. Also, the seven quality strategies--which

include PFMEAs, PPAP, APQP, MSA, SPC and Six Sigma--must

be executed flawlessly.

GM has worked hard to fine-tune its vehicle development

process, and one need only look at J.D. Power and Associates

and Harbour reports to see the results of its labor. In

2003 J.D. Power awarded GM’s new Lansing Grand River

plant the Silver Plant Quality Award; the GM Oshawa, Ontario,

plant received the Gold Plant Quality Award. But Toyota

and other manufacturers continue to improve as well. For

example, in 2003, J. D. Power recognized Korean manufacturers

as the most improved in quality. Global competition is unrelenting.

GM registered all its sites to ISO 9001, QS-9000 and ISO

14001. They’ve championed certification of top management,

engineers, quality personnel, manufacturing personnel and

technicians as ASQ-certified quality engineers, quality

auditors, reliability engineers, and Six Sigma practitioners.

GM’s mission is to be the manufacturing best-in-class

at understanding, managing and controlling variation. Variation

must be reduced in all areas of production around the stated

target, specification or requirement. The same intensity

will be expected of suppliers that plan to do business with

the automaker.

GM has benefited immensely from its registration initiatives.

If today’s challenges happened a decade ago, the company

wouldn’t have survived the competitive requirements,

marketing incentives and economic variation it’s now

experiencing. But that’s exactly what ISO 9001:2000,

ISO/TS 16949:2002, ISO 14001 and their predecessors were

designed to help companies do--provided they comply with

the standards. If not suboptimized, each of the elements

can reduce process variation even in the simplest functions.

Ford’s assembly plants still use a concept called

“incoming quality” with suppliers. This involves

a monthly meeting during which the five to 10 worst suppliers

explain to plant management and senior Ford executives what

they’ll do to improve products. If a supplier stays

on this list for more than six consecutive months, the Ford

plant can withdraw its Q1 customer endorsement.

Ford’s Q1 endorsement was originally developed during

the early 1980s. The current version includes five categories.

(Note: Most of Ford’s listed documents are accessible

only to its suppliers via a confidential Web site. Other

items are available through the Automotive Industry Action

Group at www.aiag.org.):

Capable systems. Suppliers are required to maintain third-party

registrations to both ISO/TS 16949:2002 (or QS-9000:1998

through December 2006) and ISO 14001. Also, suppliers must

pass an MS 9000 materials management operations guideline

or materials management system assessment. Ford required

suppliers to register to ISO 14001 by July 1, 2003. For

those that didn’t meet the deadline, a special letter

published earlier this year through the AIAG outlined the

steps they must take. Basically, if a supplier has yet to

comply with ISO 14001, it’s subject to losing its

Q1 status.

Capable systems. Suppliers are required to maintain third-party

registrations to both ISO/TS 16949:2002 (or QS-9000:1998

through December 2006) and ISO 14001. Also, suppliers must

pass an MS 9000 materials management operations guideline

or materials management system assessment. Ford required

suppliers to register to ISO 14001 by July 1, 2003. For

those that didn’t meet the deadline, a special letter

published earlier this year through the AIAG outlined the

steps they must take. Basically, if a supplier has yet to

comply with ISO 14001, it’s subject to losing its

Q1 status.

Ongoing performance. With the ongoing performance requirement,

suppliers are monitored for five key performance metrics:

field service actions, stop shipments, part per million

performance, delivery performance and violation of trust.

A monthly report called “Supplier Improvement Metrics”

is issued with a six-month rolling status. Suppliers start

with 1,000 points, which diminish following various requirements

violations. If a supplier falls below 850 points, it must

create action plans for Ford’s supplier technical

assistant. If these fail to resolve the issue, then Q1 probation

is initiated.

Ongoing performance. With the ongoing performance requirement,

suppliers are monitored for five key performance metrics:

field service actions, stop shipments, part per million

performance, delivery performance and violation of trust.

A monthly report called “Supplier Improvement Metrics”

is issued with a six-month rolling status. Suppliers start

with 1,000 points, which diminish following various requirements

violations. If a supplier falls below 850 points, it must

create action plans for Ford’s supplier technical

assistant. If these fail to resolve the issue, then Q1 probation

is initiated.

Manufacturing site assessment. This is an evaluation of

whether a supplier is performing to Ford’s various

operating units’ expectations. The assessment includes

planning and demonstrating manufacturing process capability,

variability improvement (i.e., Six Sigma project results),

manufacturing efficiencies (i.e., new programs improved

through surrogate data, first-time-through initiatives and

overall equipment effectiveness) and customer satisfaction

(i.e., a robust and effective quality operating system).

Manufacturing site assessment. This is an evaluation of

whether a supplier is performing to Ford’s various

operating units’ expectations. The assessment includes

planning and demonstrating manufacturing process capability,

variability improvement (i.e., Six Sigma project results),

manufacturing efficiencies (i.e., new programs improved

through surrogate data, first-time-through initiatives and

overall equipment effectiveness) and customer satisfaction

(i.e., a robust and effective quality operating system).

Customer endorsements. These state that Ford operation units

are satisfied with the service and quality they receive

from a specific supplier. In addition to the assembly plants,

suppliers must seek endorsements from other Ford groups

they might deal with, including material planning and logistics,

customer service, and supplier technical assistants.

Customer endorsements. These state that Ford operation units

are satisfied with the service and quality they receive

from a specific supplier. In addition to the assembly plants,

suppliers must seek endorsements from other Ford groups

they might deal with, including material planning and logistics,

customer service, and supplier technical assistants.

Continuous improvement. CI is a yearly assessment to ensure

that suppliers are actually improving. Suppliers must show

objective evidence both to their registrars and Ford indicating

improvement--not just change--in the way they satisfy the

automaker. This is monitored primarily through the SIM reports.

As one supplier technical assistant stated: “All STAs

are watching the continual improvement thresholds, which

suppliers must establish in 2003, with manufacturing efficiency,

variability reduction and customer satisfaction as the lead

indicators. The lean game, Six Sigma, FTT and OEE improvement,

and other quality tools are required.”

Continuous improvement. CI is a yearly assessment to ensure

that suppliers are actually improving. Suppliers must show

objective evidence both to their registrars and Ford indicating

improvement--not just change--in the way they satisfy the

automaker. This is monitored primarily through the SIM reports.

As one supplier technical assistant stated: “All STAs

are watching the continual improvement thresholds, which

suppliers must establish in 2003, with manufacturing efficiency,

variability reduction and customer satisfaction as the lead

indicators. The lean game, Six Sigma, FTT and OEE improvement,

and other quality tools are required.”

Ford has been credited with one of the best quality system

concepts in the industry, despite the fact that, during

the 1990s, the company didn’t seem to practice what

it preached. Today, it’s working toward a full partnership

with its suppliers to ensure that customers are truly delighted

about the product.

OEMs expect flawless execution in every process their

suppliers undertake. This begins with the advanced product

quality planning process and continues through service of

vehicle parts with no warranty claims. However, the purchasing

public also expects vehicles that are exciting and perform

as promised in advertising. In this regard, U.S. OEMs would

do well to heed Einstein’s definition of insanity:

doing the same thing over and over and expecting different

results.

As U.S. manufacturers continue their quest for the elusive

“silver bullet,” Japanese automakers found help

from people like W. Edwards Deming and Joseph M. Juran.

Toyota, Honda and others even opened their operations to

U.S. competitors and formed joint ventures such as NUMMI,

knowing that U.S. organizations would miss the opportunity

to improve, as Japanese manufacturers did, too, early in

their benchmarking.

W. Edwards Deming summarized his life mission in what

he called “profound knowledge” into four key

attributes: appreciation for a system, knowledge of variation,

theory of knowledge and psychology. Japanese organizations

listened to Deming and implemented and improved upon what

they learned. U.S. OEMs used Deming’s ideas for a

while, but it’s not always evident that they consistently

apply what they’ve learned. They still have an opportunity

to demonstrate continual improvement, but time is growing

short.

The silver bullet is nothing more than understanding,

managing and controlling variation. It must be reduced around

targets, specifications and requirements in every process

step, from concept through product sale.

Roderick A. Munro, Ph.D., is a business improvement

coach with RAM Q Universe Inc. (www.ramquniverse.com)

and has more than 30 years of experience in manufacturing,

automotive, service and education. He has served, trained

and consulted for many industries in the United States,

Canada and Europe, and trained or consulted with production,

nonproduction and transportation tier-one suppliers in quality

systems. Munro is an ASQ Fellow, Certified Quality Engineer,

Certified Quality Auditor, Certified Quality Manager and

a Fellow of the Quality Society for Australasia.

Ronald J. Bowen spent 46 years with General Motors,

focusing on variation reduction. He developed the internal

audit process and managed QS-9000 registration and ISO 14001

implementation and registration at one of GM’s plants.

He now serves as president of Quality Station Inc., which

provides consulting services in quality and environmental

management systems implementation and internal audits. Bowen

is a past chair of ASQ Greater Detroit Section, served as

the ASQ deputy chair for four years, is a member of ASQ’s

American Quality Congress Board, examining chair for the

ASQ Automotive Division and deputy regional director for

ASQ Region 10. He’s an ASQ senior member, and CQE,

CQA and IRCA QMS provisional auditor. Letters to the editor

regarding this article can be sent to

letters@qualitydigest.com.

|