by Radley M. Smith; Roderick A. Munro, Ph.D.; and Ronald J. Bowen

After many years of experience with the registration process and its resulting maintenance, much of the fear associated with meeting your customer’s upgrade requirements should be gone. The time available before the customer deadline is adequate for the upgrading of a system that has already been extensively audited.

Considering these facts and the history of QS-9000 registration, the goal for ISO/TS 16949 should be to develop a quality management system that promotes the continuous improvement of product quality and productivity while also supporting registration.

With this new aim, the development of a QMS will be aligned with the enterprise’s financial goals. The QMS will cease being a cost of doing business and become something that actually facilitates profitability and marketing goals.

Before diving into the upgrade process, the management committee (the chief executive/owner/plant manager and direct reports) must have some idea of the game being played. To facilitate this, we offer a radical but essential suggestion: Members of the management committee must devote one hour to actually reading ISO/TS 16949 and then spend 20 minutes writing down their thoughts on how it affects their areas of responsibility. (Yes, this means the CFO/controller, the human resources director, the IT champion and all other senior managers, as well as the one person who has ultimate responsibility for the organization and its success.)

Focusing the management committee on ISO/TS 16949’s requirements will help management realize ISO/TS 16949 is not about paperwork, procedures and records. Instead, it’s about establishing efficient processes for real-world business activities and the continuous improvement of them.

A group of experts exists that is uniquely qualified to help your company develop a value-adding QMS. Fortunately, you don’t need to interview a number of consultants or sign a contract to obtain the services of this group. The experts are your employees. They know your company better than outsiders, and with the proper tools they can develop a QMS that will support your company’s registration and be a powerful force for continual improvement.

If your company is currently registered to QS-9000 or ISO/TS 16949:1999, your employees are familiar with the auditing process. The only missing link is familiarity with, and understanding of, the ISO/TS 16949:2002 requirements. This link can be readily provided through training, preferably by your own people who have studied the document at public meetings or in dedicated sessions on your premises.

To use your employees as a resource in developing a value-adding QMS, your organization should follow 12 steps. These steps include the creation of an employee familiarity with, and understanding of, ISO/TS 16949 requirements at the appropriate time in the process.

Ask any quality practitioner to describe the most serious obstacle to improving a company’s quality system, and at least 98 percent of the time the answer will be, “lack of top management understanding and support.”

The issue here is involvement. In the past, it was assumed that a commitment letter signed by the CEO was the only thing required of top management. Unfortunately, such “commitment,” taken by itself, has little effect on employees’ daily conduct. If the upgrade process is to contribute any value, top management must be actively involved. This is actually an ISO/TS 16949 requirement.

It’s vitally important top management understand it alone is responsible for the system that controls the company’s quality and productivity. Clearly, a change in behavior in regard to the organization’s approach to the QMS is required.

Most chief executives, company owners and plant managers have little knowledge of quality, and what they do know is usually wrong. In their minds, quality is either fixed or broken. They believe quality is a matter of everyone working hard and doing his or her best. If there is a quality problem, they think someone is doing something wrong, probably out of laziness or perhaps ill will. This strongly contrasts the mindset in the typical Japanese company, where a quality level good enough for today is definitely not good enough for tomorrow. In this environment, it is believed employees will continuously improve productivity and quality if given appropriate leadership.

Most students of quality would agree with the late W. Edwards Deming, who said that at least 85 percent of quality problems result from management systems and can only be resolved through management action. However, because QS-9000 registration is perceived as having been ineffective in providing product that always meets customer requirements, management likely perceives QS-9000 as outdated.

The authors of ISO 9001:2000 understood this perception clearly. Consequently, they used the words “Top management shall…” 10 times in the management responsibility section of the standard. The intention was to identify the challenges only top management can meet.

If the upgrade to ISO/TS 16949:2002 is to achieve its goals and add value, it’s essential that the CEO and his or her managers understand and accept their responsibilities. In the case of large multiplant suppliers, the plant manager must be a champion for the ISO/TS 16949 process. Although tasks can be delegated, the responsibility for verifying the effective completion of those tasks cannot.

Consider the compelling parallels that can be drawn between quality goals and financial goals. Clearly, companies must return adequate profits to their owners. Elaborate cost analysis and tracking systems provide the CEO with real-time measurements of financial efficiency. Large staffs usually plan these systems and analyze their results. Profitability is everybody’s job, but top management still feels the need for the support of a controller’s office or finance staff.

Just as companies must return adequate profits, high-quality products must meet customer needs. This is evidenced by the continuing growth in the market share of Asian-based automakers, whose products generally have higher customer-perceived quality than the products of North American-based producers. However, in spite of this fact, North American-based producers have systematically eliminated their quality staffs. The apparent organizational strategy is that “quality, like profitability, is everybody’s job.” Training Six Sigma Black Belts and letting the employees “fix” quality is thought to be enough. It’s difficult to imagine a large automotive supplier in a financial crisis trusting a few Black Belts to turn the organization’s financial performance around.

Choosing the right people for the ISO/TS 16949 implementation team is crucial. The following criteria should be the basis for selecting team members:

Familiarity with the company’s processes and with top management’s objectives Familiarity with the company’s processes and with top management’s objectives

Familiarity with the current QMS and the third-party auditing process Familiarity with the current QMS and the third-party auditing process

Willingness to think outside the box Willingness to think outside the box

Representative on the company’s functional departments Representative on the company’s functional departments

Familiarity with customer expectations Familiarity with customer expectations

Credibility with top management Credibility with top management

Beyond these criteria, it’s important to have various levels of management represented on the team, both to demonstrate commitment and to spread understanding of the process. The size of the team can vary from three to 10 but should be reflective of the size of the business unit seeking ISO/TS 16949 registration. Although team members will generally have other day-to-day responsibilities, a significant portion of each team member’s time must be devoted to the implementation process. The best way to accomplish this is to specify a date for achieving registration that represents a “stretch”--normally six to nine months. If a longer period is provided, the first months will probably be wasted.

The team’s first job is to identify the processes that will be included in the QMS. Without reference to existing procedures, identify the steps in the process and draw a simple flowchart. Although it’s possible to use an elaborate system of symbols for flowcharting, it’s not necessary. At this point, the goal is simply to show all of the steps in the process and their relationship to each other. A large flip chart or blackboard should be used so the entire team can see the development of the flowchart, add to it, and correct it.

It’s important not to jump to process improvement while developing the flowchart. It may happen that team members make suggestions for simplifying the process before the flowchart is completed. These ideas should be captured and then deferred to step 5. Once the team has agreed that the flowchart is an accurate representation of the existing process, the flowchart should be reviewed with all associates involved in the process. Ideally, one of the team members should conduct the review so comments can be recorded and presented back to the entire team.

Training in ISO/TS 16949 requirements should take place after existing processes have been flowcharted. In this way, team members will understand how the new requirements align with the flowcharted processes. As will become obvious during training, the majority of ISO/TS 16949:2002 requirements come directly from QS-9000 or ISO/TS 16949:1999, often with no significant change. What is different is the emphasis on processes, rather than on isolated requirements.

For each process, the team should review the flowchart, keeping in mind relevant ISO/TS 16949 requirements, to see how the process can be improved. In some cases, process steps can be combined or eliminated. Normally, a trial of the proposed new process should be conducted to determine its effectiveness. Such a trial often produces new insights into the process, which can lead to further efficiencies. Although it’s impossible to set any universal criteria for process simplification, the team should be aware that the desired outcome of this process simplification is not the elimination of only one or two steps, but rather 30 to 60 percent of the steps.

Think of procedures as tools to communicate your company’s best practices to employees. The procedures should be as clear and brief as possible. Forget what your outside auditors say in regard to these procedures. If your team develops clear, brief procedures covering the “who, what, where, when and how,” they will work just fine. Contrary to what some consultants say, there is no such thing as an “ISO/TS 16949 format” or an “ISO 9001 format” for procedures. Seriously consider making the flowchart part of the procedure (although there is no requirement to do so). Inclusion of a flowchart reduces the number of words required--a huge benefit. There are also major benefits for both internal and external auditing if the flowchart is included. Auditors will understand the process more quickly and determine more accurately if process intent is being met.

One supplier developed a highly effective format that ran the flowchart vertically down the left-hand side of the page while describing each step in a brief paragraph to the right. Significantly, many of this supplier’s procedures were on a single page. Short graphic procedures such as these stand a good chance of actually being posted at the employees’ workplaces and used.

The team must consider how the new procedures should be implemented. For minor changes, a verbal review at the job site may be adequate. More significant changes may require classroom training. The rationale for the changes should be explained in terms such as, “We’re making this change to reduce the opportunities for mistakes.” Be sure to document whatever training takes place.

If the changes are on a large scale, it may be beneficial to have a limited pilot implementation. If the changes affect more than one location, the pilot could be implemented at a single location only. The results of this pilot can then support the implementation training.

It’s common for internal audits to be limited to the determination of compliance. After all, that’s the requirement. However, compliance provides only a foundation for continuous improvement. A foundation is necessary, but it doesn’t comprise the entire building. For continuous improvement, it’s necessary to seek input for process improvements during each internal audit.

Reporting internal audit findings presents the opportunity to obtain management support and a commitment of resources for process improvement. Areas such as training, equipment rehabilitation and concerns about purchased product can be brought forward and specific requests for resources made.

One good way of measuring the effectiveness of a management review meeting is to evaluate what changes occurred as a result of the meeting. What assignments were given? What degree of urgency was communicated? A management review that merely summarizes the number of audits scheduled and completed adds little value to the supplier.

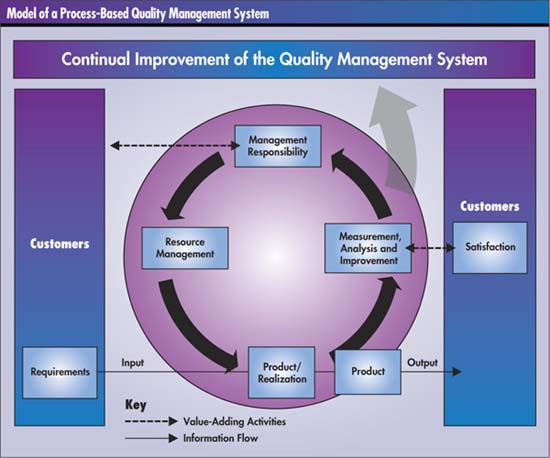

The “Model of a Process-Based QMS” in ISO/TS 16949 makes it clear that continuous improvement requires an ongoing process. Repeating steps one through 10 on a regular basis, perhaps two to four times a year, can become the method for a never-ending cycle of quality and productivity improvement.

A company that considers productivity and quality improvement of comparable importance to profitability and growth will use the ISO/TS 16949 upgrade process in a way that improves operational efficiency and not only supports registration but also the organization’s financial goals.

A company that follows the process described, aside from making solid preparations for the ISO/TS 16949 upgrade audit, will have aligned and integrated its QMS with its business objectives so the business objectives support the QMS and vice versa.

Even if your organization is currently registered to ISO/TS 16949, it would be beneficial for top management to review current processes during normal meetings to ensure the ultimate goal of meeting or exceeding customer satisfaction.

This approach will improve a supplier’s productivity, product and service quality while also enabling registration.

Note: This article is excerpted from The ISO/TS 16949 Answer Book, published by Paton Press. For more information, visit www.patonpress.com.

Radley M. Smith is group leader for automotive systems with BSI Management Systems. During a 30-year career with Ford Motor Co. he had assignments in production supervision, quality, supplier development, and product engineering. He is also the author of The QS-9000 Answer Book (Paton Press, 1999) and co-author of Quality System Requirements QS-9000.

Roderick A. Munro, Ph.D., recently retired from Ford Motor Co., where he was senior engineer in the supplier quality improvement initiative. He is currently the principal of RAM-Q Universe, a quality training and consulting firm.

Ronald J. Bowen recently retired after 46 years with General Motors Corp., where he served in a variety of quality, auditing and environmental positions.

|