| by Craig Cochran

For most organizations, process

orientation offers one of the biggest improvement opportunities

available. It also represents a huge change in the way most

organizations view and manage themselves. With process orientation,

organizations think in terms of integrated processes rather

than a confederation of functional departments. Although

there's nothing inherently wrong with managing by departments,

problems arise when they're managed semi-autonomously. In

such cases, each department manager attempts to maximize

his or her results without considering how the results affect

the remaining portions of the process. In addition, departmental

divisions cause countless problems related to communication,

coordination and resources. As a result, the organization's

performance suffers because its operations aren't structured

optimally.

Before we go further, let's clarify what the term "process"

means. Very simply, a process is an activity, or bundle

of activities, that takes inputs and transforms them into

products or output. Under this extremely broad definition,

just about any activity could qualify as a process. However,

we'll concern ourselves strictly with major business processes

--the handful of primary transformation activities within

an organization. Even the most complex organization probably

has fewer than 20 major business processes. These work together

in an integrated manner to carry out the organization's

strategy and achieve its mission.

Managing a business in terms of business processes makes

perfect sense, you might be thinking. Why would an organization

manage itself any other way? The answer is that most organizations

are structured according to functional activities rather

than processes. For example, people who perform similar

activities and report to the same manager are grouped together.

Once they finish their work, the product is handed off to

the next functional department and forgotten.

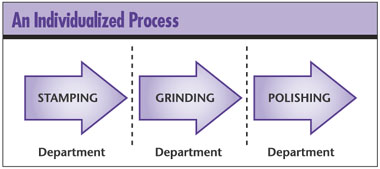

For example, consider the manufacture of widgets. The

three key activities in widget manufacturing are stamping,

grinding and polishing. A traditional widget manufacturer

divides these activities into individual departments, each

with its own manager, staff, equipment and supplies, as

illustrated below.

From one perspective, organizing the company like this

makes a lot of sense. The work is cleanly divided into discreet

activities, with specialists doing their jobs and only their

jobs. Measuring the output of individual activities is easy.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Frederick Taylor and

Henry Ford used this approach to achieve new levels of productivity

from, and control over, employees. With cleanly divided

departments, employees are focused on their own work and

little else.

Ironically, this focus is also one of the drawbacks of

the approach. Everyone concentrates exclusively on his or

her job and really doesn't understand how the work contributes

to the organization's greater goal. Departments try to excel

individually without regard to the organization's overall

excellence. Each department measures its output and its

efficiency, doing whatever it can to improve this performance.

Such a structure works fairly well when an organization

makes a large quantity of a few products and it can sell

everything it makes. The structure causes problems, however,

when the product list expands and mass customization becomes

critical. Of course, a wide product list and mass customization

are virtually the norm now, for manufacturer and service

providers alike.

Another drawback to the departmental approach is that

resources aren't easily shared across departments. Personnel

are trained to do jobs in their departments only; they can't

be redirected to activities in other departments because

they don't know anything about those activities. Even if

they did, what would be the advantage to the department

manager, who's measured on the output of his or her department?

The departmentally structured organization lacks the flexibility

to apply people where they're needed on a moment's notice.

Personnel aren't the only resources that get snagged on

departmental boundaries. Supplies and materials don't flow

easily across these divisions either. When supplies and

materials are allocated to individual departments, there's

little motivation to share resources when other departments

need them. At the very least, delays occur as the details

are worked out and managers determine how they can benefit

from the situation. The question, "What do you have

that I can use?" is often heard in such situations.

Because most managers are compensated based on their department's

performance, they can't be blamed for behaving logically.

The last important resource that has trouble passing through

departmental boundaries is information. The departmental

structure sets up a filter between information and the people

who need to receive it. Feedback about the conformance of

work between departments is delayed or blocked altogether.

In many organizations, it's forbidden for personnel to leave

their departments and interact with people from other departments.

Even without such explicit prohibitions, though, departmental

divisions pose an obstacle to personnel receiving feedback

on their work further down the line. This block reinforces

the tendency for departments to think of themselves as little

islands, operating independently of other activities.

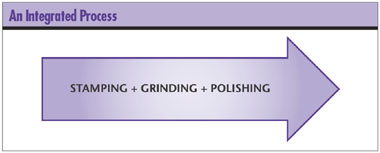

Consider how the illustration below differs from the one

we've been discussing.

The functional activities of stamping, grinding and polishing

are recognized as part of an overall process. No departmental

boundaries exist between these activities. Personnel are

cross-trained on different jobs so they can move from one

activity to the next, based on the workload. Flexibility

is built right into the structure. Because departmental

boundaries don't exist, resources also flow smoothly from

activity to activity. Information, supplies and materials

all go where they're needed, when they're needed. One person

manages the entire process and is compensated based on the

process's overall performance, rather than just one aspect

of it.

An organizational structure based on major processes makes

perfect sense, but it's a radical departure for many enterprises.

Most managers have come of age in a world where companies

consisted of functional departments, not integrated processes.

Understanding how processes function requires a different

mindset than understanding how departments function.

The missing element here is the link between one activity

and the next. In functional departments, links are taken

for granted. If each department does its part, then the

entire organization will succeed. Little consideration is

given to the links between the departments, even though

most problems occur there.

Process orientation highlights the links between activities

because the links have become a visible part of the process.

They aren't disguised by departmental boundaries. With true

process orientation, if the links aren't effective, it becomes

immediately apparent. The connections between activities

become smoother because the process's dynamic nature demands

that they continually improve.

Clear processes also encourage organizations to use teams

in the workplace. Supervision is important when people must

be pushed and directed, which happens when nobody really

understands how the overall process works. In an organization

that has adopted process orientation, everybody can clearly

see how the various activities fit together and support

one another. The relationships are obvious. People can see

and understand the results of their efforts, and supervision

becomes less necessary. Process orientation therefore promotes

self-directed work teams and team problem-solving.

In almost every way, process orientation is superior to

traditional departmental structure. Consider the following

comparison between a functional department and an integrated

process:

With a functional department, you'll find:

Specialization

Specialization

Improvement efforts focused on the activity level

Improvement efforts focused on the activity level

Each activity fully staffed

Each activity fully staffed

All personnel and equipment utilized

All personnel and equipment utilized

Little understanding of interdependencies between activities

and processes

Little understanding of interdependencies between activities

and processes

Close supervision

Close supervision

Localized communication

Localized communication

Slow feedback from downstream activities

Slow feedback from downstream activities

Metrics focused on the activity

Metrics focused on the activity

Narrow accountability

Narrow accountability

Little flexibility in the event of changes

Little flexibility in the event of changes

Competition for resources

Competition for resources

An inward-looking view

An inward-looking view

Clean divisions between management and staff

Clean divisions between management and staff

An integrated process, however, promotes:

Broad competencies

Broad competencies

Improvement efforts focused on the process level

Improvement efforts focused on the process level

Activities only staffed as necessary

Activities only staffed as necessary

Personnel and equipment used when demand requires them

Personnel and equipment used when demand requires them

Heightened understanding of interdependencies between activities

and processes

Heightened understanding of interdependencies between activities

and processes

Less need for supervision

Less need for supervision

Free-flowing companywide communications

Free-flowing companywide communications

Fast feedback from downstream activities

Fast feedback from downstream activities

Metrics focused on the overall process

Metrics focused on the overall process

Broad accountability

Broad accountability

Flexibility when change occurs

Flexibility when change occurs

Shared resources

Shared resources

An outward-looking view

An outward-looking view

Blurred divisions between management and staff

Blurred divisions between management and staff

Many subprocesses support one major business process,

but they all have the same ultimate objective: enabling

the business process to fulfill its organizational objective.

Major business processes sometimes coincide with traditional

departmental boundaries but more often cut across them.

People often become confused about where to draw the lines

between major processes. It's worth vigorous discussion

but not worth getting too hung up on. The exact definition

of each business process could easily be argued from a number

of different angles. It's important to remember that, with

process orientation, the organization is broadening its

focus and attempting to embrace a new structure. This alone

is a huge breakthrough.

Let's look at some examples of major business processes

and the subprocesses that support them.

Leadership process:

Leadership process:

- Determining a mission

- Developing a strategy

- Selecting key measures

- Communicating the mission, strategy and key measures

- Ensuring that all processes stay focused on the customer

- Analyzing data

- Making rational decisions

- Recognizing personnel for their contributions

- Representing the organization to the outside environment

- Acting ethically

Customer satisfaction process:

Customer satisfaction process:

- Conducting research into market needs and desires

- Communicating market needs and desires to other processes

- Developing the marketing strategy

- Locating potential customers

- Providing product information

- Selling

- Performing sales follow-up

- Gauging customer perceptions

- Analyzing data on customer perceptions

- Communicating to the organization about customer perceptions

Design process:

Design process:

- Understanding market needs and desires

- Converting needs and desires into design input

- Planning design activities

- Coordinating activities with all process leaders

- Developing product output that meets design input

- Reviewing the design progress

- Verifying and validating design output

- Communicating design information to other processes

- Controlling design documents

Inbound process:

Inbound process:

- Communicating needs to suppliers

- Evaluating and selecting suppliers

- Purchasing supplies, services and equipment (i.e.,

inbound products)

- Verifying the conformity of inbound products

- Ensuring the payment of suppliers

- Providing feedback to suppliers on performance

- Moving inbound products to the appropriate location

- Storing inbound products as necessary

- Optimizing the time, cost and performance of inbound

products

Product realization process:

Product realization process:

- Communicating supply, service and equipment needs to

inbound process

- Scheduling work

- Arranging resources

- Producing the product through appropriate transformation

activities

- Verifying product conformity

- Providing feedback to all activities within the process

- Packaging the product as appropriate

- Applying identifiers to the product as appropriate

- Final product release

Outbound process:

Outbound process:

- Handling of the final product

- Scheduling transportation

- Storing the product

- Ensuring preservation

- Order picking

- Truck loading

- Coordinating delivery with customers

Personnel management process:

Personnel management process:

- Determining personnel competency needs in cooperation

with process leaders

- Recruiting appropriate personnel

- Assigning personnel to processes

- Determining appropriate compensation and benefits packages

- Developing policies that result in employee retention

- Facilitating organizational communications

- Mediating conflict

- Ensuring legal compliance

- Administering programs to build competencies (e.g.,

training, etc.)

Maintenance process:

Maintenance process:

- Providing maintainability requirements to inbound process

owners

- Determining and implementing preventive maintenance

- Scheduling work in the most efficient manner possible

- Reacting to breakdown scenarios

- Performing predictive maintenance

- Optimizing infrastructure cost, timing and effectiveness

Improvement process:

Improvement process:

- Guiding the development of procedures

- Managing internal audits

- Administering corrective and preventive action

- Reporting to leadership on the results of improvement

efforts

- Facilitating problem-solving methods and tools

- Troubleshooting with customers

- Assisting in improving suppliers

- Guiding the use of statistical techniques

- Identifying and removing nonvalue-added activities

- Soliciting improvement ideas from personnel

- Ensuring personnel recognition

- Supervising the investigation into product and service

failures

Drawing the lines between business processes is something

of a balancing act. Generally, an organization benefits

when the business process cuts as broadly as possible through

the organization: however, a process that cuts too broadly

will be difficult to control. Defining the end of one business

process and the start of another is a matter of subjective

judgment and what can only be called "process wisdom."

Nevertheless, a couple of guidelines can assist in defining

the processes.

First, business process includes activities that add value

to a product in the same general manner (e.g., by acquiring

and readying the product, transforming the product, etc.).

The activities don't necessarily need to be similar to one

another, but they must work toward a common destination.

Second, business process includes activities that have

the same general objective (e.g., acquiring the best supplies

and materials at a competitive cost, transforming the product

in the most efficient manner possible, etc.).

Avoid the temptation to define processes along the same

boundaries as functional departments. The whole point of

process orientation is to combat the narrow, myopic perspectives

that functional departments often encourage. Simply calling

a functional department by a different name does nothing

for the organization.

In a perfect world, restructuring an organization along

business processes would be a simple action. Nobody resides

in a perfect world, however. Organizational changes of this

magnitude carry with them significant implications, and

usually only the most senior managers can successfully carry

them out. Even then, they sometimes fail.

Evolving toward process orientation is the best solution.

Practical actions can be implemented that will gradually

shift your organization toward process orientation. And

these can be implemented by anyone with organizational respect

and clout. The cumulative impact of the following actions

is great, but taken slowly and incrementally, they're much

easier to digest:

Determine the business processes that exist within the organization.

Determine the business processes that exist within the organization.

Compare the boundaries of the business processes with existing

functional departments to determine where conflict exists.

Compare the boundaries of the business processes with existing

functional departments to determine where conflict exists.

Develop process flow diagrams that span departmental boundaries

and depict business processes in their entirety.

Develop process flow diagrams that span departmental boundaries

and depict business processes in their entirety.

Cross-train personnel who work within the same business

process.

Cross-train personnel who work within the same business

process.

Assign cross-trained personnel to new activities in order

to build flexibility and heighten awareness of the integrated

process.

Assign cross-trained personnel to new activities in order

to build flexibility and heighten awareness of the integrated

process.

Examine incentives and objectives across functional departments.

Do they encourage improved functional departments at the

expense of business processes? Remove all incentive and

objectives that suboptimize the organization's overall performance.

Examine incentives and objectives across functional departments.

Do they encourage improved functional departments at the

expense of business processes? Remove all incentive and

objectives that suboptimize the organization's overall performance.

Establish opportunities for personnel to interact within

and across business processes. Encourage frequent dialogue.

Some of the best improvement ideas come serendipitously

through informal discussion.

Establish opportunities for personnel to interact within

and across business processes. Encourage frequent dialogue.

Some of the best improvement ideas come serendipitously

through informal discussion.

Encourage personnel to communicate their ideas for improvement.

Focus personnel on improving business processes rather than

narrow tasks and activities.

Encourage personnel to communicate their ideas for improvement.

Focus personnel on improving business processes rather than

narrow tasks and activities.

Eliminate activities that don't add value or contribute

to the effective functioning of the business process.

Eliminate activities that don't add value or contribute

to the effective functioning of the business process.

As personnel and managers become accustomed to thinking

in terms of business processes instead of functional activities,

begin reshaping the formal structure of the organization

toward process orientation.

As personnel and managers become accustomed to thinking

in terms of business processes instead of functional activities,

begin reshaping the formal structure of the organization

toward process orientation.

Craig Cochran is a project manager with the Center

for International Standards & Quality, part of Georgia

Tech's Economic Development Institute. He has an MBA from

the University of Tennessee and is an RAB-certified QMS

lead auditor. He is the author of Customer Satisfaction:

Tools, Techniques and Formulas for Success, available

from Paton Press (www.patonpress.com).

Visit the CISQ Web site at www.cisq.gatech.edu.

Letters to the editor regarding this article can be

sent to letters@qualitydigest.com.

|